They Also Serve

They Also Serve

By John McCarney

Senior Airman USAF 1973-1977

“… over Land and Ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”- Milton

A few years ago, my wife and I drove down to San Diego from Los Angeles. My son was coaching college baseball there and we decided to go visit him.

After one of his games, he handed me a large manila envelope. “Hey Pops, this is from a coach I know. He wanted you to have it.” I was totally perplexed and opened the envelope. Inside was an Air Force Academy baseball hat, an Air Force shirt and a sealed envelope. I opened the envelope and there was a challenge coin and a card. On the card was written; “Mr. McCarney, thank you for your service, looking forward to meeting you someday – Tim Dixon.” That moment set off a chain of events that changed my life forever.

I had buried any thoughts about serving in the Air Force some 40 years ago. I had thrown away all my uniforms the day I got out. Vietnam was fresh in everyone’s minds and people made derogatory comments to veterans and the Vietnam War. I didn’t want to deal with that situation. I just wanted to forget about it.

My son had obviously mentioned my past Air Force service to the Air Force pitching coach. His note and Air Force souvenirs started a series of recollections in me that swirled into a large cloud of guilt. As my wife drove back to Los Angeles that evening, I was lost in thought. We passed Camp Pendleton, the United States Marine Corp base just north of San Diego. I wondered how many young kids had come through there and valiantly gone on to give their lives.

I also thought about how I had not…

I was conflicted for the next couple of years. I had gone to the University of Oregon on a football scholarship and it hadn’t worked out. To be more accurate, I didn’t work out. I was overwhelmed and depressed. I left school. For most of my life I had been a football player. There was never any doubt that football was my calling. I was lost after I left school. I had no identity except, John the football player.

One day I walked into a recruiting office and I took an aptitude test. I scored high enough that I had my choice of several job classifications. I chose Air Force “Medical Service Specialist,” better known as a Medical Corpsman. Looking back, I wonder if I chose that job because my dad had been in the Air Force and my mom was a nurse. I wanted to make them proud, to be like them since I wasn’t going to be a football star. I served as a Medical Corpsman from 1973 to 1977, right at the end of the Vietnam War.

I was now forced to remember my service.

I completed basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. After that, I finished my Medical Corpsman technical training at Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, Texas. I was then assigned to the 13th Air Force, Regional Hospital at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines. This was the same base and hospital that the POWs were brought to after their release from the Hanoi Hilton in North Vietnam in 1973. It was now late 1974. While the Vietnam war was officially over for the United States because of the Paris Peace Accord, South Vietnam was showing signs of collapsing. North Vietnam troops were moving south into South Vietnam and the cities were falling like dominos.

It was at Clark Air Force Base that I experienced the most unexpected duty, and unknowingly, the beginnings of a guilt that would haunt me for decades.

I reported to the hospital eager to get my assignment. Most of the Corpsmen were being assigned to a Tactical Hospital. They would rotate in and out to conflicts and set up “MASH” type units for short periods of time. I was looking forward to rotating out to a combat area. I wanted to do something I could be proud of.

I reported to the Personnel Sergeant with another brand-new Medical Corpsman. We sat in front of the Sergeant’s desk as his head was buried in paperwork. There was a large white board behind him with all the different areas of the hospital written on it. When the Sergeant finally looked up to addressed us, the other Corpsman with me immediately asked; “Excuse me, it looks like there is a need on the Medical Ward, could I have that position?”

My head spun. I looked at the board and couldn’t figure anything out. I saw where there was a blank for the Medical Ward and other blank under the letters O.B. The Sergeant shook his head yes. He looked me up and down taking in all of my six-foot five-inch, two-hundred- and thirty-five-pound muscular football body. He laughed. “That leaves O.B. for you.” I nodded yes, not knowing what O.B. was. When we got up to leave, I asked the Sergeant where O.B. was, and what it was. He smiled, “Third floor, Obstetrics… they need someone to work in Newborn Nursery.”

I was floored and angry. As I took the elevator to the third floor, all I could think about was how could I get transferred away from taking care of babies. When the elevator dinged and the doors open, the cries of the babies echoed so loud, I couldn’t think. I walked towards the crying and saw Lt. Lynn Fuzz, and Captain Fannie Gaines standing in the doorway. Being fresh out of technical training school, the sight of officers made me nervous. I awkwardly saluted. Captain Gaines smiled and looked me up and down. “I asked for two Corpsmen and instead of two, they send me one big one.”

Lt. Fuzz oversaw the Nursery and Captain Gaines oversaw the whole Obstetrics ward. After a brief orientation, I was given a pair of hospital greens and for the next fifteen months, I worked with the babies.

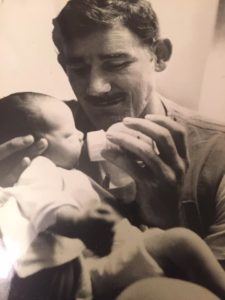

It was an extraordinary time. I went from not being able to put a diaper on a baby, to working night shift all by myself. It was a sight to behold. I was this huge, former college football player taking care of tiny two-pound premature babies that could fit in the palm of my hand.

I excelled in the Neonatal Intensive Care side of the nursery. I thrived under Lt. Fuzz’s guidance and read every medical book I could, I became like a guardian angel to those preemies. Captain Gaines and the staff pediatricians had enough confidence to let me work many a shift by myself. My duties included tube feeding, injections and draw blood work, to resuscitating the little guys and gals when the monitors went off and they forgot to breathe. I’d run over to a preemie that had stop breathing and revive them. Then I’d go bathe another six well babies at the same time. Then I’d drop everything and run to the piercing beeping sound announcing that another baby had stopped breathing. I’d place my huge hand over their bodies and get them breathing again. I knew I was doing something more important than playing football and the sting of leaving faded away.

The Stars and Stripes newspaper came by and did an article on me. One of the photos won an award because of the contrast of the huge hand against the frail, tiny infant.

In April of 1975, South Vietnam collapsed. There was fear that the mixed-race babies of American G.I.s and local Vietnamese women would face unspeakable consequences. As I worked in the hospital at Clark AFB in the Philippines, actions by others in Vietnam triggered an amazing event that would eventually lead to my guilt.

Many civilian orphanage personnel and World Airways owner, Ed Daly, took actions into their own hands to save as many babies as they could. A twenty-year-old, long-haired, hippie orphanage worker, named Ross Meador, drove a beat-up Volkswagen van to remote orphanages to picked up abandoned mixed race children. It was extremely dangerous and chaotic. We were close in age at the time and I’ve talked to Ross quite a bit over the last few years about his time in Vietnam. Ross described the events to me as, “Like Saving Private Ryan… but with babies.”

Leann Thieman, an Iowa homemaker and prospective adoptive parent, smuggled in $10,000 dollars in cash into Vietnam in her bra for food and medical supplies for the orphanages. In her book “This Must Be My Brother”, co-written with Carol Dey, Leann explains how, “instead of helping to get out six orphans… we now were going to help get three hundred out.” To quote her…” it was a great love story… an amazing humanitarian effort…”

Ed Daly was a hard punching, Bowie knife toting CEO of World Airways. He was frustrated by the red tape holding up getting the orphans out. Ross defied protocol, and with fifty-eight children that he helped load on one of his planes, Daly boldly flew the orphans to the U.S. His heroic efforts woke up the world to the crisis.

Mr. Daly passed away in 1984. I have been in contact with his granddaughter, June Behrendt, to get some perspective on the events. She had heard all the stories. She summed it up best when talking about those events by saying; “It’s complicated”. When she wrote me later, she wrote again, “…did I mentioned it’s complicated?”

President Gerald Ford authorized “Operation Babylift” in 1975. “We are seeing a great human tragedy as untold numbers of Vietnamese flee the North Vietnamese onslaught. The United. States has been doing-and will continue to do-its utmost to assist these people… I have directed that two million dollars from a special foreign aid children’s fund be made available to fly 2,000 Vietnamese orphans to the United States as soon as possible…. I have directed that C-5A aircraft and other aircraft… to care for these orphans… be sent to Saigon.” President Gerald R. Ford. 3 April 1975.

The Air Force C-5 A Galaxy aircraft, the largest cargo plane on earth, were massive. When they landed at Clark Air Force Base, they dominated the tarmac. General Paul Carlton was the Military Airlift Command Commander. He oversaw the logistics of the operation. As Medical personnel and volunteers were gathered from our base, the C-5A Galaxies were converted from military cargo planes to giant flying cribs to bring back hundreds of orphans.

A large tent city was set up to triage the babies and orphans as the planes brought thousands of them to Clark AFB. The gymnasium and other buildings were turned into shelters in addition to the building of “Tent City.” Many civilian volunteers and Air Force personnel were put in place to serve the onslaught of needy children. After their medical assessment, the children were to be sent to the United States.

Then the unthinkable happened. The inaugural C-5A flight of Operation Babylift crashed shortly after takeoff from Tan Son Nhut Airport, near Saigon on April 4, 1975 killing 138 people, including 78 orphan children.

The news was devastating back at Clark A.F.B. I remember feeling devastated and a strange feeling came over me. I felt guilty that my job assignment kept me safe while others perished doing something so valiant. I knew a couple of the medics that were on that flight that never returned. It was a small thought at the time, a thought that would linger inside of me for years. Little did I know when I left the Philippines, ironically on a C-5A transport, and headed back stateside, that seed of guilt would be imbedded in me. A certain amount of unworthiness festered inside me, and it would eat at me for the next forty plus years.

I finished my tour of duty in 1977 and received an Honorable Discharge. I had developed some circulatory issues in my legs from standing so long when taking care of those babies. It became difficult for me to stand for long periods of time and I would have to reclassified if I had stayed in the service. I had two different operations on the veins in my legs while on active duty. Today I’m classified disabled by the Veterans Administration for the conditions of my legs from those days so long ago. I didn’t pursue a medical career after leaving the service.

I still think about those orphans often. I think about their birth moms and how hard it must have been for them to give up their children to the orphanages. A desperation that I cannot imagine. And, I think about the orphans themselves landing in California or Australia with new families, to start a new life. I often wonder what happened to them and the babies I helped save.

Guilt is a funny thing. It hides within us and we never know it until it raises its ugly head. It casts a shadow on our soul and emotionally lingers like a black cloud. I can remember the exact moment where I finally dealt with the guilt. Actually, it dealt with me. A couple of years after I had received the items from Tim Dixon, the former Air Force baseball coach, an event gave me a whole new perspective of my service in the Air Force. I sat with some friends at a Major League Spring Training baseball game in Arizona on a warm night, watching the Seattle Mariners play the Cincinnati Reds at Goodyear, Arizona. At the end of the second inning, the stadium announcer asked for all Military Veterans to stand and be honored. The crowd gave us a round of applause. But I was slow to get up. My friend, Jim Gustin, who knew I had served, yelled at me to get up. Another friend, Mikey Chalmers, who didn’t know I had served, was irritated that I was slow getting up. I quickly sat down before the applause was finished.

That night, while were having dinner, Mikey was still perplexed about me not proudly standing up with the other Veterans. I’m not sure why, but as I tried to explain myself, I suddenly got choked up and tears welled up in my eyes. I had no idea where it came from. Everyone at the table became uncomfortable watching this big old guy cry. I explained that while I served, I did not feel as worthy as those that served and put themselves in harm’s way. I was safe within the Newborn Nursery, while others from my base and on the C-5A died. I just felt what I did was not as important and as honorable as what others sacrificed.

Mikey’s wife Lynda could not stand seeing me cry. She got up in my face and tried to distract me. She said, “John, think about squirrels. Don’t think about that…think about squirrels.” Her comment caught me completely off guard. I smiled and then chuckled. It worked. I stop crying. My friends went on to try and cheer me up. They said, “It doesn’t matter, you served.” They said I had gone where I was asked to go by my country and did what I was asked to do and that what I did was just as important. Lynda said, “Write down how you feel and maybe it will help you. Get it out on paper.”

I later contacted Retired Colonel, Regina Aune. She was the flight nurse in charge of that doomed C-5A inaugural Babylift flight. We talked about that fateful event when the plane crashed killing all those people. She did some amazing heroic actions that day. With broken bones in her foot and back, she saved many infants and children from that plane. Regina Aune was a young lieutenant then. For her actions, she became the first woman to receive the Cheney award. It is awarded to an airman for an act of valor, extreme fortitude or self-sacrifice in a humanitarian interest. She retired as a Colonel in 2007. Captain “Bud” Traynor and all the other surviving crew were amazing in their efforts to minimize the loss of life.

I spoke with two Vietnam War Veterans that had a huge impact on relieving my guilt. They helped me look at my service in a new light. One was Elvis Bray. He was an Army crew chief on U.S. helicopters between 1968 and 1970. He was in harm’s way in the Mekong Delta doing search and destroy mission his first tour and with a Dustoff unit in the Central Highlands his second tour. Elvis helps a lot of servicemen deal with survivors’ guilt and PTSD by helping them write their stories. He stressed to me that circumstance does not outweigh commitment. He was adamant when he talked to me and made me come away with one thought and one thought only; “YOU SERVED, be proud of it.”

The other former Vietnam Veteran that helped ease my pain was a Marine. I think his name was Danny Hernandez. He probably wouldn’t even remember me. I met him in passing at the Ace Theatre in Los Angeles while at a presentation and panel of the Ken Burns’ documentary film, “Vietnam.” Danny had served at the height of the conflict. I happened to be standing next to him in the lobby for a few minutes. We said hello and he asked if I had served in Vietnam. I said, “No, I was safe in the Philippines working in the Newborn Nursery.” He made a powerful comment that made me rethink my feelings. He said something to the effect, “Well, it makes me feel good that someone was bringing life into the world, while we were taking it out.” It rocked my thought process.

I finally was able to open up my heart and write down how I felt. It made me feel better. Everyone that I talked to including the people involved in Operation Babylift, and the Vietnam veterans told me the same thing. You served…

As the days slipped by, I kept thinking about all I had experienced the last few years. Finally, on Veterans Day, November 11, 2017, I woke up feeling different. I went into my closet and I found the Air Force shirt and hat that Tim Dixon had given me a few years earlier. I put them on and looked in the mirror. I then did something I had not done in over 40 years. I put my feet together with the toes pointing out at a 45-degree angle, stood at attention, cupped my hands and with my thumbs point out perfect, like a brand-new recruit. I snapped my right arm up to my Air Force hat with my hand and snapped off the best salute I could muster. I looked at myself in the mirror and teared up.

Standing tall in my Air Force memorabilia, I got in my car and drove to my favorite Starbucks. A middle-aged lady, who was waiting for her drink, kept staring at me. She approached and smiled. “Thank you for your service.” The barista chimed in… “Thank you for your service.” I grabbed my coffee and as I walked to my car, a young well-dressed millennial in a BMW pulled up close to me. He jumped out of his car and shook my hand. “Sir, I want to thank you for your service”, he said. I was surprised and overwhelmed. As I drove away, it became crystal clear to me. All of us who take the oath and defend our country are providing a sacred service. Chance and circumstance are not ours to judge. It is enough to know that those of us who may not have been on the front lines, or gone into harm’s way, provided an important support role supporting our brothers and sisters that do. I now know in my heart… we also serve!

Airman McCarney attending to one of the premature babies at Clark Air Force Base. March 1975

Airman McCarney feeding one of the well-babies in the nursery. March 1975

Airman McCarney adjusting monitor leads on preemie. March 1975