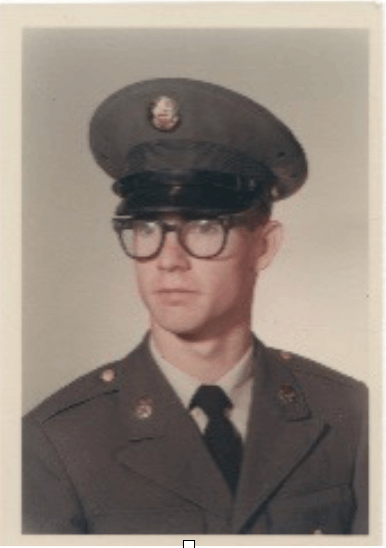

John Hollis

US Army Vietnam Veteran John Hollis

After watching Ken Burn’s “Vietnam” PBS special I decided I’d write down the recollections of my time in Vietnam. I’m not like some (my dad for instance) who can remember dates and places like they happened yesterday but using the information I’ve saved I have a fairly accurate timeline of where I was assigned and when, but the order of what happened while I was at each unit all flows together.

I have to back up to Basic Training to give context to how and when I ended up going to Vietnam.

When I joined in early March 1968 I signed up for armor (seemed like a good idea at time), but about three quarters of the way through Basic at Fort Ord near Monterey, CA Special Forces recruiters showed up and, like I have done numerous times over the years, I said to myself, “What the hell” and signed up. That voided my armor orders which the Army changed to Medic and Airborne training.

When I joined in early March 1968 I signed up for armor (seemed like a good idea at time), but about three quarters of the way through Basic at Fort Ord near Monterey, CA Special Forces recruiters showed up and, like I have done numerous times over the years, I said to myself, “What the hell” and signed up. That voided my armor orders which the Army changed to Medic and Airborne training.

I finished Basic in the top something-percent and was advanced to PVT E-2 (I think the other folks didn’t get that advancement until about the six-month point). After hanging out doing dumb stuff for a few crappy weeks the orders to Fort Sam Houston for medic training came through and it was off to Texas – I think that would have been around late April or early May 1968.

If I remember right, the basic medic course was 10 weeks and I graduated on June 28, 1968 with an MOS of 91AO. The barracks were the old open bays with red floors and absolutely no air conditioning or even fans which meant we soaked in our own sweat in the Texas humidity. The curriculum that was covered, I think, would be the equivalent of an EMT today and was primarily geared for the field medic with a bit thrown in on bed making.

From there it was three weeks at Fort Benning, GA for Airborne training. I enjoyed the heck out of it even though we ran everywhere and the barracks, probably because of the large number of guys they were pushing though, were old, poorly maintained and had no hot water. Part of our company was a group of Navy UDT guys who irritated the sergeants by saying “Uhrah” instead of “Airborne” like the rest of us. When we finally got to the jumping part I always arranged it so that I was either the first or last guy in the Stick (that’s what the Army call the guys getting ready to jump) because I hated being pushed out. I graduated on July 18, 1968 and for some strange reason they picked me to be the Honor Graduate.

When it came time to leave for Fort Bragg, NC and Special Forces training there was a glitch. After we had signed out of the training company and were ready to step on the bus two of us were stopped because admin couldn’t find an important and vital piece of paper. I don’t remember its title but it was yellow card stock with all our vital information. No one, on a Friday afternoon, knew what to do with us at that point so they told up to hang out in the empty barracks until Monday when they’d work everything out (like we believed that).

First thing Monday morning the other guy and I went over to admin, BS’d the hell out of some lady, got that yellow card, made our way to the Columbus, GA bus station where we bought tickets to Fayetteville, NC. We changed busses in Atlanta and the only thing I remember about that Southern city was we couldn’t find a bar within walking distance of the bus station.

Upon arrival, on Tuesday morning the sergeant asked, “Where you been boys?” We explained and that was the end of it. The only minor issue was that weren’t going to go through Phase 1 of the Special Forces training with the guys we’d gone through airborne school with.

At that time, the basic SF training was broken into three parts, Phases 1, 2 and 3. One was SF history, some infantry stuff, some survival stuff, etc. I think it was about three months long and upon graduation we received our Green Berets without flashes (the insignia that goes on the beret).

At that time, the basic SF training was broken into three parts, Phases 1, 2 and 3. One was SF history, some infantry stuff, some survival stuff, etc. I think it was about three months long and upon graduation we received our Green Berets without flashes (the insignia that goes on the beret).

Phase 2 with the specialty training because everyone had to have at least two specialties: Communications, Intelligence, Medical, Engineer and something else. They decided I should be a communications specialist. The only problem was that I couldn’t learn code (Morris Code). They offered me another specialty and while I waiting for that, as well the approaching Christmas leave, I got really drunk on 100 proof vodka. Three days later, when I returned to the living, I had lost that “Cock of the Walk”, “Meanest Mutha in the Valley” attitude and put in my request for some other assignment. The top sergeant told me to think it over during Christmas leave and to give him my decision then. My decision remained the same and, no surprise, my orders were for Vietnam. One funny side note. When some of the guys saw APO San Francisco on their orders they thought they were being assigned to the City by the Bay. We explained the facts of life that that only meant their mail was going to San Francisco before making its way to Vietnam.

Officially, each guy leaving Fort Bragg (or maybe just those leaving Special Forces training) for Vietnam was to be qualified on the M16 rifle and some jungle training. I didn’t get either even though I have orders saying that I qualified Sharpshooter on the M16 – which I’d never touched up to that point (all my qualifications were on the M14) and had that jungle training.

In early March 1969, after two weeks at home, I made my way to Fort Lewis outside Seattle where the Army did what the Army does and got me onto a plane with all my gear. The civilian chartered flight was packed (this was during the big buildup) and I, as a mere PFC, spent the next eight or so hours sitting between a big guy on my right and big guy on my left with the only thing to look at was the seatback in front of me.

The flight was supposed to go directly to Cam Ranh Bay but we spent the night in the Philippines because we were told the base was being mortared. When we got there the next day, wearing our shiny new green jungle uniforms, we asked about the attack, no one knew anything about it.

Even though I was airborne qualified and had been through some Special Forces training the Army sent me to the 51st Medical Company (Ambulance) headquartered outside Qui Nihon, a coastal city situated about half way between Saigon and Hue.

When first assigned, the new medic was the assistant on the ambulance and the more senior guy was the driver.

When first assigned, the new medic was the assistant on the ambulance and the more senior guy was the driver.

The day-to-day duties were to station two ambulances at the 85th Evacuation Hospital and one at the explosive off-loading site. Most of the time nothing happened so we just sat in our ambulances, but on occasion it got interesting. Vehicle accidents kept us the busiest. It was strange working on an injured GI or Vietnamese civilian with hordes of folks standing quietly, just inches away with some peering at the action right over my shoulder.

Only once did I have to respond to the aftermath of an attack. It occurred in a downtown Qui Nihon bar when a VC tossed a satchel charge into the crowded establishment, killing a bunch and injuring a bunch more – including GIs. We had to go in, check to see who was living, step over the dead and treat those we could. It was a hell of a mess. Once we were finished with that and were just settling down back at the hospital we got word that an ARVN jeep had been blown up. We raced to the scene and found one or two guys still alive in the burning jeep. After getting them to a safe distance we stabilized them and hauled them back to the hospital.

Other times we were used to transport doctors and patients to and from outlying aid stations. Beyond that it was routine Army stuff; maintain the vehicles, stand guard duty and play volleyball.

Outside Qui Nihon the Army had a major ammunition dump and an MP company oversaw security. Besides the fences, guard towers and the like close to the dump they also ran patrols into the nearby hills. I don’t know how long they had been doing those patrols with medical help but one day the 51st got a request to provide a medic for their patrols. Doing my WTH thing I, along with two or three others, volunteered. When I was packing my aid bag and rucksack my Sergeant First Class handed me an M16, the first time I’d ever handled one. It was great to have because it was much lighter than my sturdier and less prone to jamming M14 that I usually carried. When I told the SFC of my ignorance with the rifle he gave me a quick class on loading and unjamming the weapon.

This is a good time to talk about fear. Every day I was in-country I was afraid or at least extra aware. I was always thinking about where I’d dive if we were attacked and I always knew where my weapon was. But there was only truly one scared-for-my-life time – when I was on patrol with the MPs. It wasn’t that I was overly nervous about the bad guys it was the incompetence of the MPs that I thought would get me killed. Even with my little bit of training at Fort Bragg I knew more than these guys on how to prepare and how not to get lost. I know that if there had been any VC or NVA in the area they would have known exactly where we were due to noise and poor discipline. Luckily nothing happened. I did volunteer to go out with them again (shows how smart I was) but they picked another guy.

The 51st Ambulance Company had two detachments, one at Pleiku where they were attached to that hospital and the other with the 173rd Airborne Brigade at LZ English near Bong Song. They were good assignments because you were on your own – mostly. As soon as I got a feeling for what was going on I started asking for the remote assignment, I didn’t care which one.

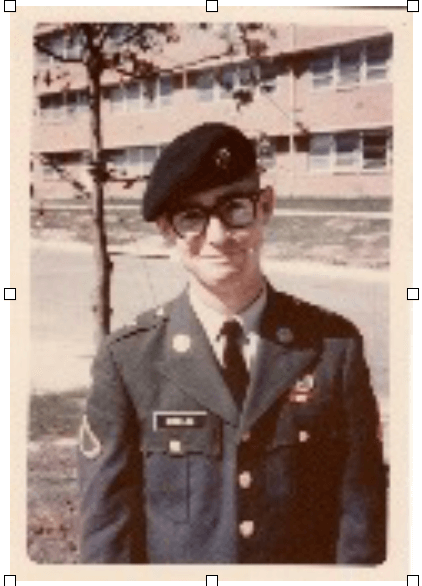

My wish came true in June ’69. My orders read, “provide ground ambulance support and assist Field Medical Regulator.” The regular duties were to transport the not-too injured or sick to the hospital in Qui Nihon about 90 minutes south, hang around and haul whoever was discharged back up north. But, of course, there were other non-official duties. The Army had a rule that only noncommissioned officers (E-5 and above) could buy hard liquor, I was Spec4 (E-4) by this time, but in the Air Force an E-4 is an NCO. What we would do was get everyone’s alcohol ration cards and cash, stop at the Air Force compound and haul the booze back to the LZ. This kept us in good standing with the cooks which meant we got fresh eggs instead of the dried crap.

Another of our duties was taking civilian causalities, after they were stabilized, to the New Zealand hospital in Bong Song. These trips were no problem during daylight but we were expected to make the trip no matter the hour and without escort. The first few night trips were a bit scary but we never had a problem so it became a routine drive. An added bonus was the beer – real NZ beer, not that 1.2 crap.

The medical compound was composed of various sleeping quarters, the aid station, mess hall and a shower. The shower had water that was refilled every morning, which meant if you were quick and weren’t doing something else and you got in there right after evening chow you had sun-warmed water. If you were late you had cold water and a cold slimy floor but if you were really late you showered in the dark.

Sometimes I wondered if anyone had a clue. When we drove back and forth between LZ English and Qui Nihon we were supposed to wear our flak jacket and helmet, we did carry our M14s as well as an M79 grenade launcher loaded with a shotgun round in case things got crazy in one of the towns. I did use the flak jacket to sit on to raise myself up and make it easier to see. One morning the LZ was hit with a few mortar rounds, no injuries or damage as far as I knew. We did our routine checks of the ambulance in the morning, loaded the semi-sick and injured into the back and made our way merrily to Qui Nihon. When we got to the hospital gate we were stopped and told we weren’t allowed in until we put on our helmet and flak jacket. Again, this was going in. I asked why. The answer, “LZ English was being mortared.” My answer, “No shit and so what because we just came from there?” The problem for me and my medic was that we weren’t even carrying our helmets. After a bunch of talk with their sergeant I did put on my jacket and they let us through. Later, when we were driving out no one said a thing about the absence of our jackets and helmets.

One event that I’ll never forget occurred at 2 a.m. on July 20, 1969. I’d driven my ambulance down to hospital in Qui Nihon on the 19th when the engine started acting up. It was late in the day so I drove out to the company to either get if fixed or check out another vehicle and spend the night. Because I wasn’t living there I had no bed and nowhere to secure my M14 rifle. Picking an unused rack, I sacked out with my hand on my rifle. In the middle of the night, for no apparent reason, I woke up, turned on the radio to AFVN (Armed Forces radio Vietnam) just in time to hear Neil Armstrong speak his famous words, “One small step for (a) man and one giant step for mankind.” Then I went back to sleep.

The aid station at LZ English was made up of Conex boxes (metal shipping containers) placed end-to-end with the sides cut out and then it was all covered with dirt for protection. The only openings were at one end with a single door and at the front, facing the helo pad, which had double doors. Each Conex was a working area. Some were for the lab, another for the single side band radio and the operator, but most were set up to treat the injured and sick.

Mortar attacks were fairly common and weren’t usually too destructive, you got used to them. For example, just outside the side door to the aid station was an outdoor movie theater (meaning a big white screen with benches) and the best viewing was in the back by the projector, so that’s where the newbies sat. If you looked, you could tell how much time a guy had been there by how close he sat by the door. The guys with more than 350 days in country could be found leaning against the door jam, just in case.

While I was enjoying my time at the 173rd’s aid station, I and three other guys from the company (all with last names starting with H), got orders to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 43rd Medical Group in Na Trang to be Medical Regulators with a report date of August 28, 1969. It was good duty, all we had to do was work the phones and move injured GIs either to recovery hospitals in-country or get them on flights to Japan for the more severely injured or sick. The guy in charge of us was a total jerk Master Sergeant.

I didn’t want to be there even though we had soft beds, hot showers, a club that seemed to be open all the time and soft-serve ice cream at the Delta Force compound downtown. (I knew it was Delta Force because they had a big sign right over the entrance). I wanted to get back to the ambulance company. To make that happen I did the right and official thing and put in for a transfer. Then the Army did the Army thing and instead of simply saying NO, the admin supervisor hid it. When a friend told me what happened I went to the Inspector General and asked for an investigation. That pissed off the detachment CO (a young ROTC lieutenant) as well as the Master Sergeant. The MSGT kicked me out of the medical regulators office and the LT made me a mail clerk. At about the same time the MSGT was coming out of the club one night drunk and got run over breaking his femur (that means a transfer out of the country). The guy was such an ass that the colonel threw an “I’m Glad He’s Gone Party.” Not long after that I had my orders back to the 51st, arriving there on Nov. 15, 1969.

When I got back north I found that the 51st had moved its base from the outskirts of Qui Nihon closer into town. Of course, the first thing I did was request to be reattached to the 173rd. It took a few months but in February 1970 I was back at LZ English.

Around this time, I found out the Army had a rule that if, at the time you left Vietnam you had five or less months to go on your enlistment your active duty was complete and, as an added bonus, you got a free 30-day leave anywhere you wanted to go. Both sounded great to me. I put in the paperwork and it was approved, which moved my departure date to October 1970.

The war, officially, was starting to wind down and soldiers weren’t being replaced. For me that meant taking on more duties. When I was at LZ English the first time the Medical Regulator (a very senior medical NCO who coordinated air and ground ambulances as well as managing triage during a mass casualty situation) was this big black Sergeant First Class who really knew his stuff. I never saw him get flustered plus he basically left us alone. But when I returned as a 22-year-old Specialist 4th Class with less than three years of service, I assumed those duties. I may have been the most experienced ambulance guy there with nearly a year in-country but I still wasn’t prepared for some of the duties.

It wasn’t too hard coordinating the air and ground transportation except when the commanding general, Creighton Abrams, decided to land his plane right when I was trying to get a Dust Off helo in to carry some very sick and injured to the hospital in Qui Nhon. So I strode out there, all 5-foot 4-inches 115 pounds of me, went to the Command Master Sergeant and demanded that they move so I could fly some guys out. You can imagine how successful I was. The thing that pissed me off the most was that they really didn’t appear to care that those sick and injured GIs had to languish while the VIPs went their merry way.

It was during mass causality situations that I found myself at the far edge of my abilities. I was the guy deciding who was treated first, last and sometimes not at all. I was literally making life and death decisions. The doctors and the other medics were too busy saving lives to be out there saying which guy needed to go first and which could wait. If a guy was dead it was an easy decision, but if he was so severely injured that it would take too much time from the doctors possibly preventing them from saving two or three other GIs, I had to make the decision that that guy had to lay there and probably die.

It didn’t bother me then because there wasn’t time to worry about each decision as the helicopters kept bringing in more injured. I just went from one to the next. It didn’t bother me later because life went on.

One of the most insane events I witnessed, happened during one of those mass causality situations. We had guys laying all over the place, in the walk way, outside and in the treatment areas when some Army PR officers brought in a buxom blond B-level actress to cheer us up. I was incredulous as I watched them step over these bloody guys as these totally out-of-touch officers tried to introduce her to us while the doctors were putting in chest tubes and the medics were starting IVs while others tended to the various gunshot and shrapnel wounds.

I wish I could remember specifics but those mass casualty times were just blurs to me.

Also during this period was the first time I came really close to being killed or severely injured. Previously the bad guys would mortar during daylight hours from a hill not too far away. If you were being observant you could see the puff of smoke and be inside the aid station before the shell even hit. But in the early months of 1970 they started getting more aggressive and would blast us at night. In response, we dug a bomb shelter that we covered with heavy timbers and dirt located about six or eight running steps outside our hooch. One night the explosions started and out we went, sprinting for the shelter. When I was about two steps into the open a mortar shell hit right beside me. Luckily, I was bent over and I watched the dirt and metal fly over me. As I dove into the bunker I stubbed my toe, so I guess I could have been awarded a Purple Heart for “injury result of enemy action.”

Like I said earlier, the extension meant a free leave, my time to go on vacation came in early spring 1970, I remember because it was still chilly at home. On the day before I was to leave the LZ to get back to the company, a nearby landing zone as well as English were hit with major artillery and mortar attacks. One of the areas hit was the other LZ’s aid station which meant we had to send our medics and a few doctors over there to assist while Dust Off choppers flew the injured over to us. I didn’t go because my duties kept me at LZ English. It was crazy. The whole day was just a haze with so much going on; injured men everywhere, none stop helos flying in and out, blood and bandages everywhere. It was well after dark, I guess sometime between 6 p.m. and midnight or maybe even later, when things finally calmed down. I figured why wait, so I hopped on a Qui Nihon-bound helo that dropped me off at the 51st. When we go there the guard towers were double manned. I yelled up asking them what was going on. They said LZ English was being shelled. I yelled back, “No shit!” and found myself an empty bed.

That leave was strange if for no other reason than the No.1 song on the radio was Peter, Paul and Mary’s “Leaving on a Jet Plane.” Everyone was very nice, they didn’t ask too many questions and everyone wanted to cook me a dinner. My folks lived in a quiet conservative area of Southern California so I didn’t experience any of the anti-war stuff. The problem for me was that I was never hungry or thirsty. The thirsty I understand, I figured my body had adjusted to the heat and humidity and knew how to retain water but the lack of eating I never figured that out. The only thing I really wanted to do was go fishing. Yes, it was cold but after much talking (and my mother stepping in) dad and I went to Lake Havasu on the Colorado River. While I don’t remember if we even got a nibble I do remember telling my dad (a career Navy man and WWII and Korean War vet) how strange it was not having to always having to think ahead of where to dive or where to seek cover.

Two other events during that leave shaped my last few months in Vietnam.

Before going over I’d opened a joint checking account with one of my siblings. That way if something happened there wouldn’t be any hassles getting my money. Knowing I had about six or so months to go I figured I’d buy a car while on leave so that it would be mostly paid off by the time I returned to civilian life. While that sibling and I were sitting in an Orange County Triumph dealership waiting to make the deal, my sibling told me we had to talk. It turned out that she’d spent almost all my money. The next day I closed that account and as soon as I got back to Vietnam I opened an account at some bank that only GIs in Vietnam used and had my money deposited there.

The other event was positive. As was true of many of the GIs, I hated those “fucking gooks” and I don’t mean just the VC and NVA. I guess it was obvious to my cousin, a Navy chief who was a veteran of Korea and Vietnam. One whole night he sat up with me as I drank beer after beer and spewed out my darkest feelings. While I’m sure I kept my little sister and folks awake as I screamed and yelled it was what I needed.

The trip back to Vietnam was 180 degrees different from the first east-to-west trans-Pacific trip. This time it was more like a regular plane ride. I teamed up with another returnee and we were able to snag the emergency exit aisle seats so we had lots of leg room and all the food we could eat. And when the plane stopped to refuel at Elmendorf Air Force Base, AK we even went into the lounge and had a drink.

Then it was back to the 51st and LZ English. During all the time, prior to this leave, no one in our company had ever been hurt (except in volleyball). But while I was gone, an ambulance was shot up and two of our medics were hurt.

Our living quarters weren’t bad at the LZ. We had our own hooch with a sitting area/bar/kitchen and each of the four ambulance guys had his own room. The duty wasn’t bad until, for some Army reason, things started to change. Word came down that hooches could only be open bay, no individual rooms and other silly stuff like that. I figured the fun was over so I asked the 51st’s First Sergeant King to bring me home. I have to say that First Sergeant King was was one of the best guys I ever knew in the Army. He cared about his men and was always a straight talker.

Once back at the company I saw that things had really changed. Because of the drastic draw down medics from all over were being sent to the 51st to complete their tours, we were overcrowded and racial tensions were surfacing. It was so bad that when two sergeant slots opened up the advancements didn’t go to the guys with the best records, or seniority, or time in country; they picked the biggest white guy and biggest black guy. At about this same time, and unbeknownst to me, my company CO put me in for an Army Commendation Medal. When it was denied because I had too much time left in-country he changed it to a recommendation for a meritorious Bronze Star with the same wording and sent it back. They approved that.

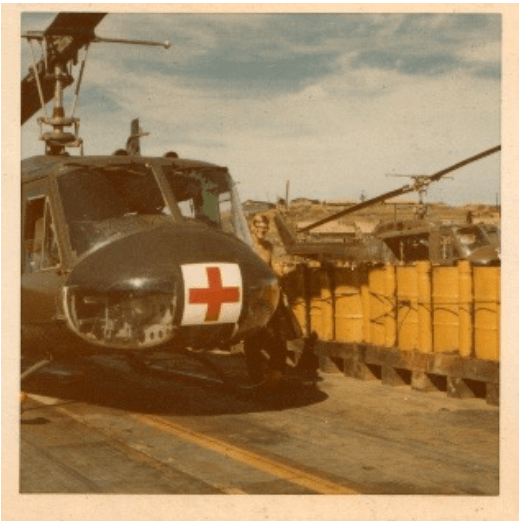

Because I’d asked to be transferred to a Dust Off company sometime earlier I’d already taken and passed a flight physical, this gave First Sergeant King a reason to get me out of there. Somehow he found an opening with the 68th Medical Detachment (Air Ambulance) in Chu Lai located in Quang Ngai province.

Two detachments were assigned together, 68th commanded by some dippy captain and the 54th commanded by Major Ernest J. Silvester the absolute best pilot I ever saw (including Coast Guard fliers that I flew with later). He was also one of the first Dust Off pilots.

Two detachments were assigned together, 68th commanded by some dippy captain and the 54th commanded by Major Ernest J. Silvester the absolute best pilot I ever saw (including Coast Guard fliers that I flew with later). He was also one of the first Dust Off pilots.

Most of our support was provided to the same unit, the Americal Division, and the same general area where LT Calley and his men massacred a village a year or so earlier. This prompted the Army to issue orders that soldiers couldn’t load their weapons until ordered to do so by an officer. Our pilots’ orders; keep them loaded. The only weapons we carried were a 38-caliber revolver, and either an M16 or an M79 grenade launcher. I handled the 79 and my crew chief had the 16, none of which we ever used.

The next three months were the busiest I’d ever been. During those months I officially logged 142 hours flight time (July-46, August-63, September-33). It was so busy that it seemed like I’d spent half my Vietnam-time there instead of just 100 days.

Most of our patients were taken to the 27th Surgical Hospital in Chu Lai.

A couple of other things to explain for clarification. The helo duty rotation was 1st Up, 2nd Up and 3rd Up. The 1st Up was the was the primary during the day, the 2nd Up was the primary at night and the 3rd Up was the back up. The way it was designed to work was that the 1st Up crew had the next day off, the 2nd Up switched to 1st and the 3rd to 2nd, because they usually had the most rest time. Also, the medic and the crew chief were assigned to a particular helo while the pilots rotated whose designations were pilot (senior pilot) and peter-pilot (co-pilot). Don’t know where the term peter-pilot came from.

It’s hard to keep things in order but I do remember there was clean air to smell, beautiful scenery and some of the most outrageous flying anyone could imagine.

When the call would come in, the duty crew would race to the helo to get it ready while the pilot got what information he could about location and the situation: in the trees, at an outpost, number of causalities, etc. and whether it was hot – meaning under fire.

On one of those mornings the major had called for an awards ceremony. As it happed we were called out on a medivac at that same time. By the time we got back the formalities were long over. That afternoon the major called me into his office and as I stood in front of his desk he tossed me my Bronze Star and said, “Here, this is for you.” That was it.

A side note: During my entire military career – almost three years in the Army and 21 in the Coast Guard I was never presented a medal or advancement in a formal, stand-in-formation type ceremony. Something I’m strangely proud of.

Another time the major called me was because of on incident at the hospital. After a mission where I’d worked hard to make sure my patient was pink and breathing when he reached the hospital this newbee and his buddy ran out to the helo and took the GI out of the helo where they promptly dropped him. I jumped out wearing about 50 pounds of ceramic bullet-proof vest and decked him. Unfortunately, the hospital commander happened to be watching and he called over to complain. The major’s orders; don’t do that in front of the hospital commander.

On more than one occasion we had to fly to the approximate location of the distress, find a break in the 100-foot-tall trees wide enough to very slowly bring the helo down between the jutting limbs, being very careful not to clip any and then zooming (so the bad guys couldn’t get a bead on us) under the limbs and between the trunks to reach the injured men. Then turning and going back the other way. I was less worried during the return trip because I was busy making sure my patient whether GI, ARVN, VC or NVA was pink and breathing by the time we landed at the hospital.

Other times we picked up guys with injuries, illness or snake bite wherever they happened to be – rice paddy, Special Forces camp, artillery base, etc.

Even the most routine mission can get interesting. One time we were assigned to pick up a GI at an artillery fire base perched on a ridge at the edge of a mountain. As we were landing the peter pilot pushed the stick forward and froze. We were going straight down, right toward the landing pad at what seemed like a 100-miles an hour. To confirm what was happening I stuck my head out the door and all I could see was the white X on the pad speeding toward us. Luckily the pilot, a guy about my size, was able to muscle the stick enough to fly us away from the outpost and down the side of that mountain. I guess the peter pilot relaxed enough that the pilot was able to fly back up and land the helo so we could pick up the guy. That was the peter pilot’s last flight.

One of the scariest thing for us were the Air Force pilots who didn’t see anything except their gauges and the ground. That meant if you were between the two you could get shot down. One of the first bits of instruction I got as a new Dust Off medic was to keep a sharp eye out for jets, that proved to be important. One day we were out and I spotted a jet and immediately keyed my mike and yelled, “Jet, 3 o’clock high!” We headed for the ground as I watched tracers fill the sky where we would have been.

But most of the time, when we weren’t working on our helos, was spent in the day room playing Hearts. It was a round-the-clock game that never ended. If I got called out for a mission another guy would take my place. We never kept count and had to replace the deck every couple of weeks because we’d wear the ink off the cards.

One of the worst nights, also the most beautiful, occurred when one of our helos was making a pick up at a hot LZ and was hit by an RPG (rocket propelled grenade) right where the tail attaches to the fuselage. The helo flipped and caught fire. Major Sylvester mustered both detachments and issued orders for all helos to be manned and ready to leave. Ours was the last to depart with the major as pilot. When we got on scene it was pitch black and the helos were stacked up in a holding pattern that resembled a upside down cone with blinking lights and at its center was the white-hot burning Dust Off chopper. Imaging looking out at these flashing red lights filling the sky like an upside-down Christmas tree with a flaming star at the top – or bottom in this case. Once we touched the ground we picked up our medic. None of our guys were injured.

It turned out that the squad had come under heavy fire, injuring a number of them and that their medic was killed as he tried to save them.

Every GI was authorized a week’s R-and-R (Rest and Recreation or Sex-and-Sin if you wish). Some guys went to Australia and others to Hawaii, I chose Hawaii. It was beautiful with lots of drinking and good food but not long enough to transition out of war-mode. I did see the 5th Dimension singing group and was propositioned by a six-foot tall prostitute.

When I returned to the Dust Off detachment I found out that things hadn’t been quiet. Just like at the 51st, while I was there no one was hurt but when I was gone it got bad. This time we’d lost two helos and a number of the guys had been injured. This meant we were shorthanded so it was non-stop flying.

The next morning my helo was 3rd Up, but with the helo count down to just three or four and the war tempo on a high note we were never able to make the hand off. This meant we flew every day until the helo had to be grounded for required maintenance. We were working so much and getting so little sleep that one night as we were flying back from a mission in a bad storm the only thing that kept me awake with the violent pitching and yawing we endured.

The most gruesome mission I went on (and one I’ve never told before) involved a squad that was under mortar and small arms fire at the edge of a rice paddy. The infantry guys were shooting into the dense forest and the bad guys were firing back while walking in mortar rounds. We couldn’t land so the pilot kept the helo hovering about three feet above the paddy while the GIs carried their wounded to us. I wondered what they were standing on to keep them out of the knee-deep mud. I looked down and saw that it was one of their own, dead and face down still doing his duty to his buddies. As I urged the guys to move faster I watched as the mortar explosions got closer and closer. Just as we took off a round hit right where we’d been.

The only other time I got close to being injured we were carrying a GI with FOU (Fever of Unknown Origin), a very common ailment. One of the things you learn as a Dust Off medic was how to check for vital signs in a noisy and breezy chopper (we never closed the doors) without any technology. With our fingers we could tell if the patient had a high temperature, had a strong or weak pulse, was breathing deep or shallow, etc. Because this guy’s fever was soaring and his breathing was very shallow I checked to make sure his airway was clear. As I slipped my finger into his mouth he went into convulsions and his jaw started to violently clench. I was just able to get my digit out before he could bite it off. I quickly told the pilot of the situation and while he dropped the helo toward the ground to get more air speed for BTW (Balls to the Wall) operation the peter pilot kept asking what was going on. By the time I answered him we were setting down at the hospital.

One of the saddest flights was a milk run to the Navy hospital in Da Nang where there were neurosurgeons. Our patient that day was a GI with one single small shell fragment that had hit him right below the skull, severing his spinal cord. As we transported him on the hour long flight my job with to squeeze the air bag to keep him breathing.

In 1970 there was no emergency medicine, no EMTs and the like in the States. There were also no air ambulances. As far as I know the state of Washington was where the air ambulance program started. One of the few visitors we had was a Washington state National Guard doctor colonel who wanted to learn. On this particular day he went up with me as we picked up a chopper-full of injured. I’d talked with him before the flight to understand his knowledge level. While he might have been a good doctor he had no experience with down-and-dirty on-the-fly emergency medicine. As I was working on the injured he asked if he could help, I said no and he had the good sense to take notes and stay out of the way.

One day we were called out to pick up a sick ARVN soldier. It was a clear beautiful day. We landed at the base of a small hill and the Vietnamese soldiers were formed up on a little rise above us. As the American advisor started to send the patient down to us one of the other soldiers took off at a sprint right for our helo. As he dove into the helo my crew chief grabbed the seat of his pants and tossed him out the other side. He never touched any part of the helo.

Another memorable mission had us carrying the remains of a Vietnamese soldier back to, I guess, his village. All we had of him was a package that was about the size of a two-pound hamburger container wrapped in butcher paper. A piece of his shattered femur had broken through the paper and stabbed me in the hand leaving me with a nasty scar that stuck around for years. But what made it memorable was that as I was climbing back into the helo they started taking off. I tried to press the mike button but didn’t have time as the cord separated from its connection. There I was looking up at the helo as it climbed into the sky while I stood in a village somewhere in Vietnam with no one around and no way to signal. They did finally notice I wasn’t aboard and came back. The pilot said I looked so forlorn as I watched them. I was the butt of the unit’s jokes for a couple of days.

As my time in Vietnam and the Army was running down it was time for the obligatory reenlistment talk, but that dippy captain didn’t pick the most inopportune time. I’d just returned from an early morning mission where the patient had experienced explosive vomiting, covering me from head to knee with his last night’s dinner. I was hungry, so as soon as I’d cleaned up the helo and repacked my gear I headed for the chow hall to get a late breakfast. On the way the captain stopped me and asked, “Hey Hollis, have you thought about reenlisting?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“What did you decide?” he stupidly asked.

“No fucking way in hell,” I said and walked off to eat my delayed meal.

He didn’t ask again.

One my next-to-last flying day, and the pilot’s last flight, we were sent out to an ARVN unit. It turned out that they had multiple injured. We just stacked them in, knowing it would probably be better to get them quickly to the hospital than being gentle with them and having them wait for other helos to arrive. With us nearing our maximum weight we lifted off and clipped a tree, luckily with the skids and not a blade. I did ask the pilot if he was trying to kill us. After off-loading, we spent the next couple of hours just cruising around taking in the sights.

Finally it was time to leave.

After I checked out of my unit I looked around for a driver, the jeeps were all gone. So I said, “Fuck it” and started walking. It took about an hour to get to the terminal. It didn’t really matter because the war was now behind me and I was in no rush. There was no particular time I had to be anywhere. I knew there were lots of flights going to Tan Son Nhut Air Base and lots of flight back to the states.

The flight back was very different for the last three trans-Pacific trips. The first one going to Vietnam was packed shoulder to shoulder with soldiers. The second was more like a commercial flight. The third, my return to Vietnam was laid back and comfortable. But this final flight had kids, white kids, with parents and all that entailed. Not only that, it was a milk run. We stopped everywhere; Japan, Okinawa and I don’t know where else. It took us 24 total-hours to get to Seattle.

The environment at Fort Lewis was totally different. In early 1970 everyone was friendly, everything was clean, the chow hall was open all the time serving steaks or anything else you wanted. This time, nothing was open, the troops handling the paperwork were surly, and there was nothing to eat. It didn’t bother me much because all I wanted was to get the hell out and get home. When they asked us questions everyone was nervous that they’d give the wrong answered and be held over. I didn’t even care that my DD214 wasn’t entirely accurate. We all did the paperwork as fast as we could, when we were told to stand in this or that line we did. In just 24 hours we got our orders, our plane tickets and our Class A uniforms and then didn’t hesitate when it was time to hop on the bus.

The bus took us to a side entrance to the terminal at SEATAC airport to avoid any possible issues with civilians.

My tickets took me to San Francisco where I changed into khakis and threw the greens into the bathroom trash because I hadn’t worn a tie or tight clothes in almost two years and didn’t want to start now. The most memorable sight in SFO airport was this very well-endowed woman wearing a large scarf for a blouse without any support undergarments. There she was ambling along swinging side to side.

My next stop was Los Angeles International where I hopped a small commuter plane to Riverside Municipal Airport. Luckily a fellow passenger was going to Hemet (a small city located at the base of the San Jacinto Mountains) which was still 25 miles from home. I walked across the city, about two miles in the chilly October air, hoping to catch a ride up the mountain to the village of Idyllwild and home. Again luckily, there were two highway patrol units at the Chevron station on the east side of town. And luckily again I’d gone to college with one of the officers three years before. Officer Pete Cole had me call my folks and have them meet us at the intersection village called Mountain Center. My folks were a bit surprised because in my last letter to them I said I’d be home sometime in the first week of October because that was as specific as I could be.

There I was back in civilian life with no time to relax. The first thing I did was buy a car; a little red Datsun 1200 with a top speed of 85 miles an hour. My older sister had held off her marriage until I got home. It was drive here and there carrying stuff and people for the wedding.

I had to have a job to get some money and fill time before restarting school in January. Again, no time to relax.

Once at school it was study and work with very little time to socialize. I did try to join the VFW or American Legion, but they didn’t want us around. I think they thought we were all druggies and baby killers.

In the second semester (fall semester 1971) I did get to know folks, primarily Vietnam vets who were, of course, older than the majority of the other students at the community college. We didn’t talk much about our experiences. Our group consisted of two guys who had been Marines, another was a Navy corpsman who served with the Marines, an Air Force guy stationed in Cambodia, a Special Forces guy and me. There was little talk about the war, we just wanted to get on with life, which included girls, study, work and the Friday night parties. Eventually we all we our own ways. Three of us went back into the service. The Special Forces guy went back to that and made a career of it, the younger of the two Marines went into the Air Force and retired as a major and I went into the Coast Guard where I retired as Warrant Officer.

Looking back, I figure it took me a full year to mentally come back to “The World,” to where I wasn’t being hyper vigilant and all of the other learned responses that kept you alive in a war zone.

Two incidents occurred during that time. One happened while a buddy and I were driving though Death Valley in the middle of summer. It was hot and we’d been drinking a bit but I wasn’t even buzzed. I was driving just like I’d done as an ambulance driver with my arm out the window and one hand on the wheel when, for no apparent reason, I was suddenly surrounded by green rice paddies and mountains. My buddy said I pulled my little truck over to the side of the road and just sat there with a blank look on my face. He said that after about five minutes I was back and we drove on.

The other was more frightening, and still affects me. I was student body president of our community college and this one kid had been bugging me for months. I was only 5’4” and 115 pounds and this kid was about 5’6” and probably 130 or 140 pounds. I don’t remember what it was but he said something that just set me off. I blacked out and the next thing I remember is that I had him by his collar, holding him a foot off the floor. I immediately dropped him and he sprinted for the door. I asked my vet friends who were in the room with me why they didn’t intervene. Their answer; I seemed to be taking care of things. But it scared me to no end that I could go berserk like that and lose all control. Even today I hate getting into arguments for the fear that something like that could happen again.

Even in the Coast Guard where it was obvious I’d been in Vietnam because my ribbons were right there on my chest, so one said anything or asked any questions. It wasn’t like it was ignored, it was just a non-issue. My youngest niece once asked me if I was ashamed of being over there because I never talked about it. I told her I wasn’t ashamed it was just that no one had ever asked me about it and I wasn’t going to bring it up.

In the late 1980s I went with my folks and first wife to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. I was a little nervous about how I would react. It turned out that I felt very little. I can only assume it was because I didn’t know anyone whose names were inscribed there. No one I knew was killed. The closest I came to that was a fellow medic I’d been with in the 51st who had gotten a transfer to a combat unit. While on patrol he’d stepped on an anti-personnel mine and had all the meat blasted off the back of his body. The last time I saw him we were carrying him, in a full body cast, to a plane carrying him out of the country.

I did earn an Air Medal for my time with Dust Off. About six or so months after I returned home I received this card informing me of the honor and asked if I wanted to have it presented to me in a formal ceremony. I, very impolitely, wrote in large red letters, “Fuck No” and sent it back. They still mailed it to me.

I learned a few lessons of course. There’s the usual about hard work, etc. But there was also

Don’t sweat the small shit

Do your job despite the dumbasses that might surround you

When deciding whether to do the hard or dangerous stuff with folks who want to be there or the easy stuff with the pretenders and draftees – always go with the tough folks who want to be there, it’s safer.

I also learned that I work just fine on my own. As the ambulance driver, Medical Regulator or Dust Off medic; I was on my own most of the time even amongst all those soldiers. In later life as a photojournalist in the Coast Guard I was often on my own. In civilian life I was on my own as the editor of a weekly paper. And at the end of my working life I was on my own as a photographer and features writer.

One final comment: My dad gave me three pieces of advice before I went to Boot Camp: Keep my mouth shut, bowels open and don’t volunteer for anything. I kept my bowels open.

John L. Hollis

CWO3, U.S. Coast Guard (ret)

High Point, NC

October 2017