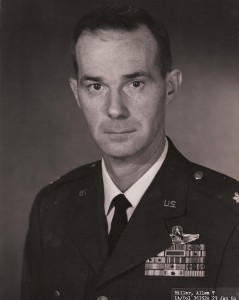

Lt. Col. Allen Terry Miller, USAF ret.

UNCLE SAM WANTS YOU

After graduating in June 1941 from the College of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Wash. with a bachelor’s degree in political science, I didn’t need to worry about how I was going to put all that knowledge to work for me. While my long interest in world geography and history made the foreign service look to be an interesting a career to pursue, that would have to wait. The military draft had been in force for one year so I was sweating out a call from Uncle Sam to come join his Army. While waiting, my Uncle Harry Rosenzweig in Monroe, Wash. hired me to paint his house, a skill acquired from my father who owned a paint store in Spokane. He had been serious in seeing that my brothers and I knew how to handle a paint brush so he sent the paint over from Spokane in 5 gallon cans like a professional painter would use, i.e., white lead, turpentine, and linseed oil (no color pigment since Harry wanted a white house). It was quite a chore to get the materials properly mixed by vigorous hand-stirring with a wooden paddle; also this was before rollers came into use and bristle brushes were the way to go. Harry’s wife had died in 1940 and his four kids were gone from home. He had a job at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe so I painted during the day and in the evening we would go out and ride on his two big horses. He was one grand uncle, full of stories of homesteading in the sagebrush plains of Eastern Washington before there was irrigation. He lived to be 100!

After graduating in June 1941 from the College of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Wash. with a bachelor’s degree in political science, I didn’t need to worry about how I was going to put all that knowledge to work for me. While my long interest in world geography and history made the foreign service look to be an interesting a career to pursue, that would have to wait. The military draft had been in force for one year so I was sweating out a call from Uncle Sam to come join his Army. While waiting, my Uncle Harry Rosenzweig in Monroe, Wash. hired me to paint his house, a skill acquired from my father who owned a paint store in Spokane. He had been serious in seeing that my brothers and I knew how to handle a paint brush so he sent the paint over from Spokane in 5 gallon cans like a professional painter would use, i.e., white lead, turpentine, and linseed oil (no color pigment since Harry wanted a white house). It was quite a chore to get the materials properly mixed by vigorous hand-stirring with a wooden paddle; also this was before rollers came into use and bristle brushes were the way to go. Harry’s wife had died in 1940 and his four kids were gone from home. He had a job at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe so I painted during the day and in the evening we would go out and ride on his two big horses. He was one grand uncle, full of stories of homesteading in the sagebrush plains of Eastern Washington before there was irrigation. He lived to be 100!

Before I could finish that job, I was summoned to report to the draft board in my hometown of Spokane so I went out on US Highway 2 with my thumb out and got a nice truck ride across Stevens Pass–beautiful views of the mountains and the original right of way and tunnel of the Great Northern RR– and checked in as ordered. I wasn’t all that enthusiastic about going into military service but with the draft in force it was inevitable. One of my best college friends Bert Cross was already serving and with the hostilities in Europe not going so well for England, the United States was doing everything to help our ally short of outright going to war The father of my grade school chum Dick Crowther was on the board and with his influence I was given the opportunity to apply as an aviation cadet in the Army Air Corps program for the training of pilots. I sure liked the idea of being a pilot and being able to fight from the sky rather than carrying a rifle in the mud. So I went out to nearby Geiger Field to take the examination for cadets. I passed the physical okay but in the last section on personality traits I was dumb enough to include the information that I used to, along with my brother, walk in my sleep. That turned out to be a no-no as a qualification for pilot, but the draft board kindly gave me time for the Pentagon to review my application and decide if I was worth the risk of flying airplanes. After letting me sweat it out, the Pentagon, apparently having decided the problem was not that serious, saved the day in a letter dated January 1, 1942 accepting me into the Army Air Corps.

During the wait, I had been living at home with my parents, the only child in residence. At the suggestion of our next door neighbor Earl Baughn, an electrical engineer with the local power company, I got temporary work with the Washington Water Power Co. inventorying electrical transmssion lines that ran through the Okanogan country, a neat job walking in the orchards in the bright, blue fall weather, counting utility poles, transformers, and such things, and gorging on the famous Washington State apples. On the afternoon of that day of infamy, Sunday December 7, 1941, I happened to be back at home listening to the New York Philharmonic concert and, when the music was interrupted by a special announcement, heard the stunning news of the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor and Hickam Field by the Imperial Japanese Navy.

YOU’RE IN THE ARMY NOW

On January 5, 1942 I was sworn into the US Army Air Corps and joined my brother-law Dick Bowden in uniform. He had taken the ROTC course at Washington State College, where he had met my sister, and was called up as a 2nd Lietenant in the Air Corps in 1941. My two older brothers were draft exempt: Gale (F.G.) was at the Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton repairing damaged ships from Pearl Harbor and Stuart (J.S.) was with the Northern Pacific RR in Livingston, Mont. keeping materiel and people moving. Once the preliminary induction steps were concluded and with travel orders in hand to the training base at Bakersfield, Calf., I boarded the Union Pacific RR train to Portland, transferring there to the Southern Pacific RR. That was really exciting because I had never been that far from home before and to top it all, I got to ride on the glamorous Daylight streamliner. Preflight training was at Minter Field in Bakersfield where I entered Aviation Cadet Class 42-H. We went through “boot camp†living in tents, drilling and studying aeronautics and military discipline, and making new friends who were mostly from the mid-West. It was a revelation to be in that beautiful San Joaquin Valley with the citrus groves in blossom and the snowy Sierra Nevadas in the background. We were glad to be issued two pairs of new uniforms, a heavy one to deal with the chilly California mornings and a lighter one to change to as the day got warmer.

In March we took the train for the short ride north to primary flying school at Tex Rankin’s famed aeronautical academy at Tulare where I learned to fly in the Stearman PT-17A, an open cockpit, bi-plane with tandem seats, student in front, much noted for its maneuverability. I soloed with no trouble and managed to get through with only one ground loop (an unintended swerve after landing) in that notorious groundlooping machine–I even did it without dragging the wing which usually got one washed-out of the program. The solo tail spin was really exciting! Loops and rolls came handily enough for me but not for many others– the “washout†rate was about 50%. Those eliminated from pilot training were evaluated as to suitability for either training as navigators or bombadiers with the chance of remaining in the officers program.

As cadets, our training was based generally on methods used at the US Military Academy so at Rankin Academy we were first classified as lower classmen and treated as such. We received some instruction on how “officers and gentlemen†were expected to behave. This included not only military courtesies among the ranks, but also close-order drilling, as well as how to avoid V.D! A good part of the barracks life was to be ordered around by the upper classmen which, at least for us, was done good-naturedly. For instance you had to be able to recite your service number backwards (mine was 19705725) and to hit a brace—a very stiff standing-at-attention with your chin tucked in tightly. And we had to learn all three (3) verses of the Army Air Corps song and be able to sing it at command of an upper classman Then in four (4) weeks we became upper classmen and it was our turn to deal with the “dodoesâ€â€”the vernacular for the new guys. It was in Tulare on Saturday nights when I first learned about the joys to be had in the wide open bars. (Washington State’s liquor laws did not permit public drinking except for 3.2 beer). I’ll never forget one place where I first heard Glenn Miller’s orchestra playing “String of Pearls†on the juke box.

In May we went across the Valley to Gardner Field at Taft for basic training in the Vultee BT-13A, a low- wing aircraft with tandem seats, closed cockpit, and fixed landing gear. It seemed a great step forward to get into a plane with 50% more power, so much so it was nicknamed the “Vibratorâ€. There had been civilian instructors for primary, most of whom were real pros, some from World War I. In basic we had Army instructors; mine was a taciturn Texan who didn’t like instructing—he wanted combat. We did a lot of cross-country flights and goofing off so I sailed thru; the washout rate was about 30%.

In July we were off to advanced flying in Arizona at Williams Field just south of Phoenix. One of my classmates had a car and five of us piled in for a stopover in that glamorous metropolis, Los Angeles, and then an all-night drive to the new station. We were checked in immediately with no chance to tidy up, so the photo taken for my I.D. doesn’t show me at my best (check my scrap book). Also in another photo I measured out at 6ft. 3 in; in actuality standing straight as possible I never topped over 6ft.1.3/4 in. It was tremendously hot at “Willie†Field but as the natives said it was “dry heat!â€; “air conditioning†was provided by water coolers with fans installed in the windows (the locals called them swamp-coolers) to provide some relief in the stifling hot wooden barracks. We trained in the Curtis AT-9 and the Beechcraft AT-10, both twin-engine aircraft with side-by-side seats and fixed landing gear. It was miserable to get into a plane that had been sitting out in the heat all day and a great relief to get up in the cool air: As for the planes, once you got used to worrying about two engines, the training was pretty routine, “washout†rate about 10%. While our location was a bit distant from the scenic part of the state, whenever possible I would sneak in extra time to take a look at the wonderful sights to the north such as the Grand Canyon and the great meteor crater. From the designation of the planes I picked up “A.T.†as my nickname. Notice how that follows the tradition set by my brothers—as well as my dad who was known as “F.E.â€. In later years as happens with red-heads some people started calling me “Red†and some like Pappy Spears and Spider Nesmith came up with “Pinkyâ€.

A SECOND ‘LOUEY†WITH WINGS

On 27 August 1942, a date well ingrained in my memory, I graduated as a pilot and got my silver wings, my 2nd Lieutenant gold bars, and was commissioned as an officer and gentleman, with serial # O729354. Before leaving Phoenix I shopped at the Goldwater Department Store and bought an officer uniform—the well-liked pinks (trousers) and greens (jacket a.k.a.blouse) and a fancy bill cap which was too nice for the combat “fifty-mission crush†look. After a short leave in Spokane to show off my splendid new hardware, I reported to the adjutant at McChord Field near Tacoma along with eight (8) other of my classmates. We were told to report to the commander of the P-38 squadron. He turned out to be a rather short type, typical of what fighter (then called pursuit) pilots were supposed to be so they could fit in the small cockpits. When he looked up and saw nine (9) six-foot and taller guys, he told us to get the heck out of there and report to the bomber squadron. And so it happened I lost my chance to fly the famous Lockheed P-38 Lightning. That probably was fortunate because years later when I was assigned to a fighter-bomber squadron in Korea I found that fighter pilots live a far different life than the one I was comfortable with after being assigned to the 42nd Medium Bomb Group to fly coastal patrol in North American B-25 Mitchells and Lockheed A-29 Hudsons. It was great being back in that area- my college stamping grounds– hiking around Mt Rainier with my friends Prof. Frank Williston and Esther Waterman, and introducing my other co-ed friends to my fellow officers. My cadet buddy John Martin even fell in love with Pegge Simpson and married her when he returned from Adak.

In those days we were sweating out more enemy attacks from submarines and spent endless hours flying in designated areas covering the coast from Cape Flattery almost down to the California border. I did this from September to February 1943, saw lots of blue water but nary an enemy anything. That is not to say that the Japs (excuse the term but that’s what they were called) didn’t attack the coast on several occasions from submarines and balloons with explosives in them. We also underwent combat training and were sent to the bombing range at Tonopah, Nev. which happened over the Christmas Holidays. Boy howdee, was it ever cold there in unheated barracks but the evenings were hot, spent in the nearby gin mills. The locals were pretty gun happy and one of our guys nearly got shot over an episode with a local female. The first of the year in returning to patrol duties we were transferred to Astoria Airfield near the Oregon coast to be closer to our ocean patrol area. While there were a lot of “socked in†days at McChord Field (familiarly called “McFogâ€), we spent a lot of time in soggy Oregon playing cards and just plain staying in the sack.

INTO THE FRAY

More B-24 heavy bomber crews were needed in the 30th Bomb Group at March Field at Riverside, Cailf. so along with several others I was transferred there in February 1943 and assigned as copilot on a nine-man B-24 crew. The other crew members were 2nd Lt. Roger Putnam (pilot), 2nd Lt. Floyd “Goldie” Amundson (navigator), 2nd Lt. Bob “Dyxe†Dyxin (bombardier), TechSgt. Mahfooz George (engineer and top turret gunner), TechSgt. Myron Albert (radio operator), StaffSgt. Ernest “Buddy” Bryson (ass’t radio operator and side gunner), StaffSgt. Edward “Duggan” Doyle (tail turret gunner), and StaffSgt. Hutchen “Hutch†Hammond (ass’t engineer and side gunner). For bombing practice our crew spent several weeks on temporary duty (TDY) at Palmdale Airfield, adjacent to Muroc Dry Lake Field (now Edwards AFB), where experimental aircraft like the ill-fated Northrop flying wing were tested. We not only saw it on a number of flights before it crashed but also some weird aircraft, like the first jet powered planes with fake propellers, which didn’t prove out. From March Field we flew a number of night flights out to San Clemente Island to get used to ocean navigation and firing the .50 cal.guns which had every fifth round as an incendiary so you could see if you were hitting the target. As typical young men, we officers insisted on getting in on the gunnery action. I should add that I managed to enjoy plenty of social life. In Riverside was the famous Mission Inn which was a hangout for fliers and my cadet buddy Bob Lockwood and I did our part in maintainingt its reputation for that. Also being not that far away from Los Angeles I took in some of the famous night spots there –the Ambassador Hotel’s Coconut Grove with Freddie Martin’s orchestra, Ciro’s and the Hollywood Hotel’s bar—all gone now!.

In June we got orders assigning us to the 11th Army Air Force with headquarters at Elmendorf Field in Anchorage, Alaska. More USAAF forces were being sent there after the Japanese attack on Dutch Harbor in June 1942, which had been repulsed but immediately followed by their capture and occupation of Attu and Kiska Islands at the end of the “Chainâ€. They were the only U.S territory ever taken and occupied by an enemy force and thus became the targets for a sustained air campaign to recapture them. This occurred at the same time as the battle of Midway and is consequently little noticed in the history of WW2. Our contingent was entrained in mid-July for the Port of Embarkation at Ft. Lawton in Seattle where we waited for onward transport to Alaska. With my brother Gale living in Seattle while working at the USN Shipyard in Bremerton, I had many enjoyable nights with him on the town. This was the first time that he got to know me as someone other than a little brother who was 12 years younger. Of course, I had to show off my brand new .45 calibre pistol with some unauthorized target practice in the surrounding woods. Also my parents came over from Spokane to help celebrate my 23rd birthday on July 21st which was held at the Angevine’s (my brother Stuart’s in-laws) home on Lake Samamish.

Finally the venerable USS St. Mihiel, a transport from WW1 days, was ready for us to board and we sailed out of Seattle for the 9 day voyage to the Aleutians stopping en route at Dutch Harbor and then on to Adak Island. The cantonment there was in pretty good shape by that time; the runway had been built on a reclaimed lagoon and paved with pierced-steel-planks (PSP), and temporary buildings called Jamesway huts (like the better-known Quonsets) had been provided for fairly decent living quarters. The poor fighter air crews on Amchitka had to live in miserable tents. By May Attu had already been recaptured after a bloody sea-assault and prolonged fight in the snow covered mountains. Kiska was under daily attack by B-24s, B-25s, P-40s (it was neat to run into one of my aviation cadet buddies Pete Ramirez flying a P-40 Warhawk), and P-38s. In addition to the missions I flew with my regular crew, I had the chance of flying with several different crews, one with my buddy Bob Lockwood who had preceded us, and got in five extra missions. This is not to indicate that I was being foolhardy as we encountered practically no opposition from the ground and never from the air on any mission. This was reported by every crew after each mission but plans to assault the island were not to be denied; a large ground force of U.S. and Canadians had been prepared to attack the island and did so in mid-August. As we suspected the enemy had vanished, unknowingly evacuated under cover of bad weather and at night. And so the campaign to kick the Japs off U.S. territory was completed. My official flight record shows I had 21 flights from August 4 thru September 9, 1943, some 15 of which were attacks on Kiska, the others as training. During this time we enjoyed fairly good weather for which we were very thankful as we did not have to experience the ferocious wlliwaws with 100+ knot winds which the region is infamous for.

Since there were fair-sized USAAF and USN forces in the northern Pacific theater of operations, our intelligence staff (mainly my future friend Larry Reineke, the inveterate keeper of records) investigated the situation to determine if they could be used to carry on an offensive against Japan from the north. Working with USN cohorts, Reineke found military installations on the Japanese-held Kurile Islands. These became our next targets, the main one being the army base and naval port on Paramushiro Island. It was some 700 miles from Attu, our takeoff point, making it one of the longest missions to be flown during the war entirely over the open seas with temperatures so cold one could live only a short time in the water if forced to ditch or bail out.

Starting in June three Paramushiro missions had been flown monthly with varying degrees of success before we were scheduled for the next one on September 11, 1943 (that “ 9/11†was bad news too). We were part of a force of seven (7) B-24s to fly at 18,000 feet and twelve (12) B-25s to fly “on the deckâ€. At the pre-mission briefing we were told that in case of bad luck it would be okay to land in Siberia even though the USSR had a non-agression pact with Japan making it a neutral in the Pacific War. As a matter of fact one of the B-25s from the Doolittle raid in April 1942 had landed at Vladivostok and the crew had been interned. We were tail-end Charley in the B-24 formation, taking-off in the dawn’s early light from Attu with our group commander standing at the end of the runway with his swagger stick in hand just as the words of our favorite song, “The Man Behind the Armor-plated Deskâ€, describes him. (See appendix for more info). Soon after take-off we encountered mechanical problems when the far left (# 1) engine started losing power and we began to fall behind. When it finally did quit, the propellor couldn’t be feathered and kept windmilling. This can be very serious because in time things can get hot and start an engine fire that can’t be controlled. Then the engine to the right of the cockpit (# 3) began to fail and we couldn’t hold altitude. By then the rest of the planes had reached the target, dropped their bombs, encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire and attacks by Zeros resulting in the loss of our lead ship crew with the squadron commander Major Frank Gash. We were so far behind and losing altitude and even after jettisoning the bombs, machine guns, bombsight, and anything else that wasn’t nailed down we continued to descend over the icy dark-blue Pacific Ocean. Since the Norden bombsight was top secret, the bombardier had the duty to see that it didn’t fall into the hands of the enemy. So in accordance with the book, bombardier Bob Dyxin detached it from its mount in the nose compartment and hauled it over the catwalk in the bomb bay and through the crawl space at the rear compartment where he drew out his .45 pistol to shoot out its vital parts. The bullets ricocheted around the compartment much to the distress of the gunners and they insisted that he desist and simply toss the thing overboard where it was pretty sure no one would find it. Still losing altitude, pilot Roger Putnam discussed the situation with me and together we decided to land at the airfield at Petropavlosk about 100 miles away on the Kamchatka peninsula rather than risk ditching in the COLD North Pacific waters where chances of survival in the icy water was estimated to be 15 minutes. Our navigator Goldie Amundsen charted the course and took us directly to the little brick-paved Soviet airfield near the city. The pilot of another B-24 also landed at Petropavlovsk. As for the B-25 attack at deck level, two (2) were shot down and six (6) others were so shot up or running low on fuel that they also elected to land at “Petroâ€. Thus there was a total of 51 American souls far from home in the far reaches of Siberia with no means of getting back.

STUCK IN SIBERIA

After landing we were relieved of our sidearms and walked over to a building with a mess hall at the little Soviet airfield station. It got pretty confusing with the language difference although one crew member of Polish descent could understand a lot of what was said. Finally some food was rustled up—can’t remember too well but fish was prominent. Eventually transport was found to carry us into Petropavlosk to a army headquarters building, consisting of a two levels with admin offices, dining hall, kitchen, and several big rooms which became our bedrooms—15 guys I think in each. Life there was very routine, we were not allowed to leave the area and with no sports area we were left to find reading material and play cards. Our two majors, B24 Gordon Wagner and B25 Dick Salter, compared dates of rank to determine who the commander of our ragtag outfit would be. B25 won which was just as well, although he was pretty “G.I.â€, he had a calmer head on his shoulders than B24 who was a sort of a smartass in that he was proud to have played for the NY Giants football team. At any rate it was not going to be easy to command a diverse group that had been brought together in a situation not covered by regulations As it turned out Salter did an admirable job using common sense and good judgement in getting along with our Soviet allies.

Although it was hoped the Soviets would permit our people to covertly pick us up and return us to Adak, they decided to intern us in order to carry out their role as neutrals in the Pacific war as they were required to do by international agreement. Their entire effort was based on defeating the Germans on their western front which left everything east of the Urals pretty much undefended. Consequently they would have been hard put to counter any Japanese aggressive moves north from Manchuria in case the Japs wanted to retaliate on a violation of neutrality.

Our chief concern was whether the news of what had happened to us was known to our units in Alaska and more importantly whether our families had been informed. During the mission we had maintained radio silence as required so we didn’t know what the returning crews had reported about us when they were interrogated (debriefed) back at Attu, although Major Wagner had transmitted a message that he was going to land in Kamchatka. Major Salter tried to find out if the US embassy in Moscow had been contacted but with the language problem there was no way to find that out. Unbeknownst to us at the time, on September 22, 1943 Army Hq had sent a telegram to our families to the effect that we were missing in action since September 11th and if further details were received they would be notified. Later when I got back home, my mother told me that a few days afterwards a man who identified himself as an FBI agent appeared at the front door and told her that I was safe and being held in a “neutral†country and they must keep that news hush-hush. Then they receved a letter dated October 21th from Army Hq confirming this and emphasizing that it was all VERY confidential; even more welcome they were told they could send letters to us via the Pentagon. As it turned out we did carry on a correspondence and seven (7) of my heavily censored letters got thru but I never received any from home. Later I was able to reconstruct the parts of my letters that had been censored—these are now in my scrap book.

To help overcome the boredom at Petro, at dinner we were served “spirits†which turned out to be about xxx proof alcohol–pretty rough stuff but helped raise our “spiritsâ€. A doctor appeared from somewhere and checked to see if we were okay. According to Russian custom that baths are required every seven (7) days in summer and ten (10) in winter, we were taken to the Turkish-type bath in town where we washed off with caustic soap and had fun whipping each other with the reeds supplied to tone up the skin. Also we were taken individually into a room where we were questioned by someone, obviously NKVD, about our background. For instance they wanted to know what my father did and why I was in the Army. As internees there was no reason not to talk, as opposed to POWs who could give only rank and serial #. At any rate I don’t think they learned anything of military importance.

Then the big day came in early October when a four-engine Martin flying boat landed in the bay and we were driven to the wharf in town and loaded aboard. We flew across the Sea of Okhotsk to Okha the city on the northern end of Sakahalin Island which had been ceded to Russia after WW1. After supper, we were ushered into a large room to be bedded down for the night. A few hours later somebody yelled out that something was crawling on him, and soon others joined in the uproar and when the lights were turned on the place was found to be infested with bedbugs—so no more sleep that night. In the morning we took off for Khabarovsk up the Amur River which bordered Japanese-occupied Manchuria on the south. We were taken to a Red Army rest camp where we ran into a number of Soviet pilots and had a chance to play volleyball with them. After a stay of several days we were told that three (3) C-47 type transport planes equipped like American DC-3s with 21 seats were ready for onward transport. We were divided into three (3) groups by crew with each assigned to one aircraft to leave a day apart–our crew being assigned to the last one. We were headed for our permanent internee camp near Tashkent in Uzbekistan. With no air navigation system in that rugged country the plan was to fly along the Trans-Siberian RR stopping each night at a military airfield. It was amazing to see all the US aircraft being supplied from Nome by the Alaska-Siberian lend-lease program, mostly fighters like the P-39 and P-63 that the Soviet pilots loved for low-level attacks; the twin-engine A-20s and B-26s were also popular for the same reason. The Soviets didn’t care about other bombers at that time as there were no German population centers or “strategic†targets to bomb.

The first night we got to Chita where we were warmly welcomed with a lavish party with plenty of “spiritsâ€. This was to happen at each stopover which included Irkutsk (on Lake Baikal the deepest lake in the world which I hoped to get a good look at but didn’t), Krasnoyarsk, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Alma-Ata, Frunze, and finally Tashkent. While refueling at Balkash I saw the fuel being pumped by hand from barrels with the ethyl anti-knock lead poured in afterwards. And at Alma-Ata, located at the base of the Tian Shan mountains, we were permitted to hike up a gorgeous valley where we saw a train of camels one of whom turned an evil eye and spat on me—it probably took offense at my bushy red mustache. Finally arriving at the Tashkent airport we boarded a bus and drove several miles east to the village of Vrevskaya where the town schoolhouse had been turned over to us as our home away from home–we called it familiarly “the Farmâ€. It was quite livable with a large recreation room with piano, a dining room and kitchen, large bedrooms accommodating 12 men (officers and enlisted segregated of course) and private quarters for our two majors, the Soviet major C.O. and his lady friend, a doctor, and 3 women translators headed by Nona a very polished woman from Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and Sylva and Olga as younger assistants. There was a working staff of cooks, waiters, and charpersons with our enlisted men doing KP duty. There was also one Soviet guard an older 3rd Lieutenant who patrolled the grounds with a rifle at night.

The place was surrounded by collective farms and had a large field where we did set-up exertcises, drilling just to keep in practice, played volley ball and baseball with a ball and bat contrived by ourselves. There was a privy out back with a hole in the floor and wooden footprints to brace yourself on; you had to bring your own paper which was not all that easy to come by. Most of us suffered from diarrhea at one time or another so the place was very much in use. Nona had a supply of paregoric which she administered freely with “Theez medezin eez veree good for youâ€. For baths we were taken into the little town to the public bath, sorta like at “Petroâ€. A barber came frequently for shaves and haircuts. We were given safety razors to do our own shaves and some grew mustaches and I and several others had our heads shaved to help keep clean. We were allowed some freedom and one of our delights was to walk down to the village and watch the daily train come through and also to frequent the bazaar where delicious fresh fruit was for sale. Most of us had money and it was easily converted at the rate of 120 rubles to $1. The official rate was 5 to 1 and our shrewd navigator Floyd Amundsen figured he could convert his dough at the going price and when he got home convert it back at the official rate. Most of us were too ready to buy the good melons, grapes, and other fruits to do that and didn’t go along with his thinking. But sure enough he was right! as he later got a good payoff at the high rate when we returned to the states.

So we settled in to make the best of the situation. We were allowed to write letters home and to receive letters and packages. As it turned out our letters did go out heavily censored but I never received any of the stuff mother sent me. But life was not dull. As mentioned there were three female translators who among other things gave Russian lessons. One of the airman could play anything you could name on the piano so singing was big. There was also a record player with USO records so Major Wagner the ex-Giant who had good legs taught dancing lessons making for lots of laughs in dancing with each other. There were quite a good number of books in a makeshift library and I took on reading all of Shakespeare’s plays, so I can say I’ve done that but it goes without saying that one needs help in understanding all those archaic words. And need I mention there was a lot of card playing both bridge and poker. When Thanksgiving came my crew wanted a special dinner appropriate to the occasion and we were permitted to visit the nearby farms to buy chickens as substitute for turkey. Nona told me to go up to a farmhouse door and say to the occupant in my best Russian “kuritza prodayateâ€?—“chicken for saleâ€?—and sure enough we were able to get enough for the cook to serve up a suitable feast. Sometime earlier the Soviets had realized we needed replacements for the clothes we had been wearing so we were measured for shirts and trousers to be made out of a heavy khaki woolen material and these were finally delivered in late January. I still have mine stashed away in the cedar chest, needless to say my body no longer fits them. Also of interest about clothing, our radio operator, Myron Albert, was Jewish and expert in Yiddish, that common language spoken around the world. One day while at the bazaar he happened to strike up a conversation with a Polish Jew who happened to be a tailor. They became quite friendly and some of us were able to have the tears and holes in our clothes taken care of. This episode later became the inspiration for “Return to Vrevskayaâ€, a novel written in 2003 by my friend Andy Scott.

Finally in early December the US military mission in Moscow sent a telegram with the news that Maj. (Dr.) John Waldron would be coming to check on our situation. After several delays he arrived just before Christmas and was warmly greeted. Besides bringing very welcome toilet articles, books, and magazines, he was able to make a cursory medical check on each of us and found that we were in “fairly good†health. His visit was limited to only two days but it brought a feeling of relief of knowing that US officials were aware of what was happening to us. With Christmas coming we were delighted to have the things he brought, especially the bourbon whiskey making for a cheery Christmas Eve.

THE MAD DASH TO THE BORDER

Then in early February we received really good news. The assistant military attaché Lt. Col. Robert McCabe arrived to announce that we were to be moved to an airfield on the Caspian Sea to receive U.S. airplanes flown up from the Persian Gulf for delivery to the front It made a lot of sense to put us to the kind of work we were trained to do and we greeted that news with cheers. The trip was to be via train and each of us was given a pillow slip filled with food like bread, butter, sugar, hardboiled eggs, tinned meat, etc., enough to last several days. Then we were taken down to the railroad station and boarded on the two final cars of the daily passenger train. The route was westerly along the famous silk route of Marco Polo fame. We rolled along for two days passing through Samarkand and Bukhara where I got a chance to get a glimpse of some of the fabulous buildings and the storied Oxus (Amu Darya) River traversed by Alexander the Great in his conquest of Central Asia. In the middle of the second night after we were all asleep, we were wakened and told to report outside. Our cars had been uncoupled from the train and we were alone in the middle of a desert landscape with a full moon above. A trainman was looking at the wheel carriage on our car and motioned that it had a “hot box†and couldn’t continue. Col McCabe explained what was going on: it was all a coordinated USSR-USA plot to let us “escape†to Iran. There were five (5) G.I. trucks standing there, one with gas and food, and the others with side benches and floorboard covered with straw to carry 15 men each. The side flaps were kept down, we were not allowed to look out in case we were being watched. Looking at the map you can see the road crossed a range of the Tian Shans and was so crooked the drivers had to go back and forth get around some of the turns. When refueling we were allowed to eat and stretch our legs and “restâ€. After something like 45 hours later we arrived at the large USArmy camp in Teheran. Dead tired, we were admitted to the hospital for a quick checkup and given a dinner of rich food– steak and ice cream, and the works–much too rich for our deprived guts, with the expected consequences. Two days later after getting our backpay we boarded an ATC C-54 and were flown to Cairo for the night. With all the new wealth in their pockets the poker players had a great game that evening. Next day on takeoff we got a quick look at the pyramids and Sphinx on the leg to Tunis with a refueling stop at Bengazi in Libya.

As part of the process in returning us to the US, we were designated as Special Army Air Forces Detachment 1 to conceal the fact that we had “escaped†from internment. We had fabulous treatment while laying over in Tunisia. We officers were quartered in a marvelous Arabian-style villa called Nejma Ezzhora (the Star of Venus) in the little Arab town of Sidi-bou-Said on the coast. The villa’s owner was a widowed English baroness who lived in the upstairs “belvedere†loft. She said that she had managed to stay there throughout the war and when the Germans were in charge of the area, the villa was used personally by Gen. Rommel, as later did Lt.Gen. “Tooey†Spaatz when he was commander of the USAAF Mediterranean Air Forces (MAAF). He had recently moved out as the allied forces had fought their way up through Sicily and then to Italy making the place available for us. The Baroness Bettina d’Erlanger was a delightful lady who loved bridge so some of us whiled away many happy hours with her and her lady friends— Mimi was one of these and the sparks flew between us. I kept up a correspondence with both of them afterwards and the baronss sent me the watercolors of the villa which I have enjoyed all these years. Also she sent me the French book in my library “Le Collier de Jasmin†(The Lei of Jasmine) which contains details on the villa—too bad I didn’t take my French courses more seriously so I can enjoy the text as well as the paintings.

We had our own G.I. vehicle to use freely, except we were told not to go to the casbah in Tunis which of course was the first thing we did—it wasn’t mysterious or anything like the one in the Charles Boyer movie but I did find a parfumerie and bought a bottle of Chanel #5 for my sister. Another point of interest, at least to the historians among us, was the nearby site of ancient Carthage that was completely destroyed by the Romans in 146 B.C. (I had to look that date up). Even better we were allowed to go over to the airbase and hop rides to Italy. So I went sightseeing to Naples to see Mount Vesuvius (it was erupting so the railroad to the summit was closed) but I did visit Pompeii and saw the red light part of town and the explicit frescos which had been among the first part of the ruins to be dug out after the A.D. 79 eruption . Also I had a chance to attend a performance of the San Carlo Opera—“Pagliacci†and “Cavalleria Rusticana†with a cast that had seen better days. Our stay in Tunis extended for just over 30 days, thus when we returned to the USA we could show a record of doing a tour in the Mediterranean and avoid saying anything about the Aleutians or our stay in the USSR. We had to acknowledge the confidentiality of that experience and sign a paper pledging not to reveal what had happened to us. Of the 61 members of my “escapee†group I stay (or stayed) in touch with Floyd Amundson, Bob Dyxin, Gerry Green, Buddy Bryson, Dugan Doyle, Benny Black, Charlie Hanner, Joe Kerns, Harry Koepp, Larry Marx, Jim O’Dair, Roger Putnam, Vladimir Sabich, and Dick Salter.

Note: Details of this experience are in the book in my library “Home from Siberia†by Otis Hays. I (and others) assisted him in his research by providing my scrap book mementos of the episode. I have three (3) other books relating to this story: “The Thousand Mile War” by Bryan Garfield (author of the movie “Death Wishâ€); “The Strange Alliance†by Maj.Gen John Deane (head of the US military mission in Moscow); and “Report on the Russians†by W.L. White the well-known war reporter and son of William Allen White of the Emporia KS newspaper. And not to forget my original copy of “Return to Vrevskaya†by my friend and talented writer (along with his square-dance calling skills) Andy Scott, a novel based on the experience with the Polish tailor in Vrevskaya.

I collected this library several years after the war and it gave me considerable insight on what happened. Although we crews were together for many months, we never talked together about the circumstances of the disastrous bombing mission. Some years later I got to wondering if we had done the right thing by breaking off our attack on the enemy and seeking refuge in the USSR. After all we had signed up to expose ourselves to enemy fire and were financially compensated for that danger by receiving a 50% increase in our monthly pay plus having a $10,000 life insurance policy. My pilot friend Roger was married with a son but I was a freewheeling bachelor with no particular reason to value my life. Although our B-24 was in bad shape, we still could have tried to get to the target and use the bombs as intended. And if we had succeeded, we might have made it back to Attu. I don’t remember being really frightened for myself ( I believed in my mother’s teaching “ God is in chargeâ€) but there were others to think about, most particularly the loyal crew members several of whom were married. With Roger as pilot it was his responsibility to make decisions and with my concurrence I think he did make the correct one.

Incredible as it seemed this was not the finale of the “Internment Story.†At the reunion of the 11th Air Force Association in Colorado Springs, Colo. in October 1992, with several members of my internment group present, we were told that we had been awarded the Prisoner of War medal and the Ass’t Chief of Staff of the Air Force was there to pin it on us. It was neat to have retired Colonel Robert McCabe, the assistant air attaché who had lead us out of internment, there with his Russian wife whom he had met in Moscow. It seems that some one had made the case to his US Representative to pass legislation that we had actually been “held captive in Siberia†and were therefore entitled to that honor. Along with several others like Dick Salter, I have never felt comfortable about this, but what’s to do about it! As an ex-POW I am entitled to extra privileges by the Veterans Administration as regards medical treatment.

THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE HOME

So as even the best of days must end, we packed up for the ATC flight to Casablanca and after a couple of nights there including a visit to Rick’s Café (for real), on April 7, 1944 we boarded the USS Billy Mitchell for the nine day crossing of the Atlantic to Newport News, Va. There we were kept at the nearby Kecoughtan veteran’s hospital for an intensive interrogation by a special intelligence staff from the Pentagon. Their object was to find out everything they could from us about the USSR which to them was high on the list of possible future opponents. Then each of us was given travel orders to report to the Army base closest to home which in my case was Seattle. I rode the Great Northern RR to Seattle whence I had departed for the Aleutians the preceding July. It was pretty neat to realize I had circumnavigated the globe in nine months traveling via every kind of transport available: military ship transport from Seattle to Adak; B-24 bomber fom Adak to Petropavlovsk; Martin flying boat from Petropavlovsk to Khaborovsk; Soviet C-47 from Khabarovsk to Tashkent; train from Tashkent to near Ashkabad; G.I. truck from near Ashkabad to Teheran; ATC C-54 transport from Teheran to Tunis and then Casablanca; military ship transport from Casablanca to Newport News; train from Newport News to Seattle and in the process “lost†a day in my life when crossing the international date-line. After reporting in, I was given a 30 day leave, spending it in Spokane with my parents and friends, as well as orders to report to the Recreation & Redistribution (R&R) Center at Miami Beach for reassignment. In getting to Florida I joined Roger Putnam and his family who were from Salem, Ore. in driving his 1940 convertible “4-hole†Buick across the country. Gasoline was rationed in those days and you needed to have special stamps to buy it. He was able to get more than enough for the over 3000 mile trip and through my good friend on the Spokane ration board I got the same amount so we were set for the rest of the war.

The R&R Center had taken over several of the hotels right on Miami beach and I along with the others roomed at the Caribbean Hotel, one of the nicest I had ever seen. We had one week for relaxing in the wonderful spring climate and playing in the surf during the day and in the bars during the nights. For our next assignments we were restricted from being assigned outside the continental U.S. (CONUS in G.I. terms) and given our choice of what base we desired. Most of us liked the idea of ending the war in Florida so picked the AAF Tactical Center (AAFTAC) at Orlando. Our whole bunch ( including one of the crew members from the Doolittle raid who had been interned and repatriated after their raid on Tokyo in 1942) was congregated there and assembled on the parade ground where the AAFTAC commander, a 3-star type, gave each of us a promotion to the next grade along with the medals we had won in the Aleutians, either a Flying Cross or Air Medal. In my case I got the silver bars of a 1st Lt. and an air medal with one cluster for my combat missions. We were also required to sign and carry on our person another memo stating, along with the overseas restriction, that the nature of of our overseas assignment was secret and we were not to reveal anything about it to anybody particularly the press.

I spent the rest of my WW2 career at Pinecastle Field (now Orlando International Airport). There along with fellow-internees “Dykes†Dyxin, “Goldie†Amundsen, “Benny†Black, Charlie Hanner, and Jim O’Dair, I was fortunate to join fellow fliers who had completed overseas assignments– Dwight “Spider” Nesmith, Kermit “Pappy” Spears, Aldo Cerone, John Houston, J.K.Neast, Sam Parisi, and Bob Pudelwitts. We were a close knit group all of whom, except Nesmith, were bachelors living together in the temporary wooden bachelor officer quarters (BOQ) on base. There were four (4) to a bare bedroom with cots and a washroom outside. I lived with Dykes, Goldie, and Benny and having withstood the internment experience together we got along great. Some of us have remained in very close touch like having reunions starting in 1989 on the 50th anniversary of the B-24. The Orlando area was a perfect Florida haven in those days, beautiful serene housing areas among the many lakes, a peaceful town center with nice hotels and restaurants, and nothing like traffic problems now experienced with neaby Disney World. Orlando Field was an older base with permanent facilities and the officers club was a magnet for most weekends. There was an outdoor dance floor paved with a huge star and the place got lots of use. I met Jeanie there. She as did many women whose husbands were serving overseas, volunteered to help entertain guys like me and we enjoyed many a time together. V-E Day was a particularly raucous evening as later was V-J Day. Among the several married officers in my outfit who rented homes in town were the Nesmiths in nearby Winter Park. Much to their consternation we loved to drop in on them after being out late and play with baby Ingrid. I also had the pleasure of meeting my first cousin-once-removed John Miller who was stationed at the nearby USN base at Sanford and taking him up for a ride.

At the AAFTAC there were four separate airfields with squadrons of each type of combat aircraft: Pursuit (now called Fighter)–Lockheed P-38, Republic P-47 and North American P-51 types; Attack Bomber– Douglas A-20; Medium Bombers—North American B-25 and Martin B-26; Heavy Bombers–Boeing B-17 and Consolidated B-24; and Very Heavy Bombers—Boeing B-29 and Consolidated B-32. Our Squadron D with 4-engine bombers was tasked to prove out different tactics in the use of airpower with high-altitude bombers. At first I flew in the B-24 with a little time in the B-17 and then got upgraded to flying the brand-new very heavy bombers, Boeing B-29 (Superfortress) and Consolidated B-32 ( Dominator). While their basic mission was still high altitude precision bombing , with more powerful engines they could both do the job much better—flying with heavier loads, faster, and farther. The B-29 was pressurized so oxygen masks were not needed ( you could smoke if you had ‘em!) and the guns could be fired from a central position. Since these two innovations could not be guaranteed to work in combat, as a backup the B-32 was also built without them. As it turned out the Superfort worked just fine so only about 100 Dominators were built and we had several of them.

With the tempo of the war increasing we worked with the folks at the Air Proving Ground Command at Eglin Field on the Florida panhandle and the Army Aberdeen Proving Ground Command in Maryland.. Some of the missions were flown with a mix of our 24s with the neighboring squadron of 17s that didn’t work out since they couldn’t keep together at altitude; as a result in combat each type was flown separatel. In trying different bomb patterns for beach assaults we flew a mission off Vero Beach with a load of 100# bombs several hooked together on the same shackle to increase damage to the target, but at the drop point they got hung-up and the flight engineer had to get into the bomb bay and literally kick them out—obviously that wasn’t tried again!. We also experimented with the first “smart” bombs which could be controlled in flight; for this there was a radio transmitter controlled by a joystick the bombardier could use to transmit a signal to visually direct the bomb to the target, but of course this was useful only in the clear weather. The bomb bays of several B-24s were converted to a classroom with several radar sets installed to be used to teach inflight target identification; with all the lakes in central Florida and the nearby coasts on each side it was rather easy to pick out landmarks to simulate bombing points. There wasa big problem flying in the hot afternoon weather when the cumulus clouds were forming– that made for VERY turbulent air below the clouds. After flyng in those conditions for a couple of hours and trying to hold course and altitude you were beat! We also experimented with the early versioms of instrument landing systems—GCA and ILAS. These were an unbelievable improvement over the old system consisting of radio beacons to be identified by code and then to pick up and follow the “beam†to the airfield—quite a demanding procedure. While we were never apprised of the results of our work, we hoped that our efforts went a large part of the way in winning the war in both Europe and the Pacific, particularly in softening up the beaches for the assaults by the ground forces.

There was an Army anti-aircraft outfit nearby and we would fly at night to give them practice in using their powerful searchlights to locate and track us. If the flight was on a Saturday night we could look down and see the lit-up big star at the officers club and would try to see who could land soonest and get over to the action at the club. And then there were the annual hurricane evacuations. In those days it seems the weather patterns always included the passing of at least one hurricane across the Florida peninsula and Pinecastle was right in the middle of that. So along with the other units we would fly our bombers to safe haven at fields in mid-country; Salina, Kans. is one place I remember where we took over the bar one night with Pappy Spears playing his guitar.

There were two notable occasions involving cross-country flights. One was in September when I received the sad news that my father had died and a B-24 was set up for me to fly to Spokane with John Houston to attend his funeral. My dad was a dedicated Mason and his “brothers†conducted a full-on burial ceremony—very moving. My mother held up very well as we knew she would and on our return flight we “buzzed†her as she stood waving her apron out in front of our home on Grand Boulevard! Then we managed to overnight at Lowry Field in Denver where my old pilot friend Roger Putnam was stationed—great to see him and his family again.

Then there was the time in February 1945 when I planned a flight to Spokane. As mentioned, I had met several desirable women who had set a fire in my heart, but they were married with husbands overseas and I wasn’t about to try to break up a marriage. Then with the example of the happily married Nesmiths and other flying buddies spurring me on, I got to thinking about college days and Eleanor “Tommy†Thompson. Starting back at Spokane Jr. College in 1939, we had dated a lot, had great times together, and stayed in close touch over the years. At this time marriage was not in her plans as she had gotten her masters degree in social work and had a fine job at Lakeland Village, the institution for mentally retarded kids in eastern Washington..Nevertheless I decided to fly to Spokane and see if I could talk her into matrimony. Unfortunately I chose to do it in February, not remembering that it was still real winter weather up that way. En route with Bob Pudelwitts as copilot we ran into a fierce cold front and in trying to fly over it, got iced up. The No.1 engine failed and wouldn’t feather (deja vue all over again), the radio direction finder failed, we got lost, and finally found a cow pasture to land in. While there was no real damage to the plane, it couldn’t be flown off the rough ground. So my boss, Major Hank Fisher, flew over from Pinecastle to pick us up and that was the end of romance for then. We later heard that a temporary runway was built and the plane repaired and flown off.

A CIVILIAN AGAIN

I liked my life in the military service but didn’t consider it as a career opportunity at the time; our family had never been involved with that profession. Mother was an out-and-out pacifist and except for Dick Bowden there was no tradition for me to follow. As a matter of fact we were always proud that Grandpa Rosenzweig had avoided being conscripted into the German army by immigrating to the U.S. in 1865. On the other hand Grandpa used to tell about his father being in Napoleon’s army and he seemed proud of that!

So what happened was that during internment I had had a chance to see what a dynamic country the USSR seemed to be and believed it was going to be friendly with the USA, as President Roosevelt had indicated by calling Josef Stalin “Uncle Joeâ€. With this in mind I got the notion to become an expert on that country and get into foreign service or something similar. Thus I mustered out of the service in October 1945 and in heading home got a memorable ride to Kansas City with Pappy Spears who was driving there with his sweetheart Maryada who later became “Mammyâ€. From there I hitchhiked to Shreveport, La where brother-in-law Major Dick Bowden was stationed at Barksdale Field. It was great getting acquainted with my nieces Katy Lou and the twins Frances and Elizabeth. I bought Dick’s Chrysler Royale to drive the rest of the way home to Spokane by myself. As part of the mustering out process I was promoted to captain and given a 90-day leave. I joined the local reserve unit but didn’t stay around to do anything for promotion credit as I was gung-ho to get enrolled in Russian studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. Thus my World War 2 career ended after almost exactly 4 years and I was on the verge of facing untold opportunities in a “brave, new, peaceful worldâ€.

APPENDIX

This is the story behind our prized song “The Man Behind the Armor-Plated Desk†which became one of the best known songs of World War 2 and was later parodied by air crews in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts. In January 1943 Col. Earl DeFord became the commander of the 11th Bomber Group. His problem was that his predecessor Col. Bill Eareckson was a pilot ready to fly anything with wings and he did, risking his life unsparingly several times. Col. DeFord was almost the opposite; on one mission to Kiska he flew along with Capt. Lucien Wernick and when somewhat short of the island gave Wernick the order to circle over Rat Island while the formation went in to attack the target. Wernick was so flabbergasted that he very likely vented his rage by writing the song—strangely its authorship has never been confirmed one way or another.

THE MAN BEHIND THE ARMOR-PLATED DESK (sung to the music of “The Strip Polkaâ€)

Early in the morning when the engines start to roar,

You can see the old goat standing in his double Jamesway door, (1)

Just a-sweating out the take-offs as he’s always done before,

The man behind the armor-plated desk.

When the phantom fleet’s reported, (2) who inspires our attack,?

Who sends deck-level battle wagons (3) from his armor-plated sack?

Who says “Hundreds may not sink them, boys, and some may not come back�

The man behind the armor-plated desk.

When the lead ship starts to shudder and the end seems near at hand,

Who is flying on the sofa with his headset on command (4)?

Who says “Climb up on top, boysâ€, with a the mixed drink in his hand?

The man behind the armor-plated desk.

Four times he’s led us out there and four times he’s led us back.

But he circles o’er Rat Island (5) while we go in to attack,

Who says “I’m hard but fair, boys, and allergic to ack-ack�

The man behind the armor-plated desk.

CHORUS “Take ‘em off, take ‘em off!†cries the man from the rear,

“Though the runway’s socked in solid, still the target may be clear,

You’ve been her thirty months now, and you’ve got another year!â€(6)

Cries the man behind the armor-plated desk.

Numbered notes:

1. A prefab building (similar to the better known Quonset Hut) used for flight crew quarters on Adak Island– double doors for the brass (that’s a joke!)

2. Japanese fleet targets were elusive and sometimes fictitious.

3. B-25 and B-26 medium bombers were generally flown at low levels—or “on the deckâ€.

4. The “command†position on the radio was used for in-flight communications.

5. Rat Island is located about 20 miles southeast of Kiska and was used as the initial point (IP) where the planes form up for the run to the target.

6. There was no set duration for tours of duty.

Author’s Note

This has turned out to be a work-in-progress because after sixty (60) years my mind keeps slowly cranking out more stuff. I started this on July 22, 2008, right after my 89th birthday which seemed to inspire me to take this on. This version is dated October 12th, Columbus Day, and I intend to keep adding to it as long as I can.