Vietnam War Story

Over a slice of Nancy Young’s apple pie, I learn about love and war

A candy striper’s Lily of the Valley-scented letters represented a sliver of saneness for Marine Bill Young, who, at the time, was a machine gunner in Vietnam.

“When the mail came in, it was a big deal; it was your only connection with the real world,” Bill recalls, nearly 49 years later. “You’d get these letters, and they’d have a perfume smell.”

Newburgh, Indiana, native Nancy Market was the sweet-scented sender. She didn’t know Bill at first, only that he was the weapons platoon leader of a friend of hers “in country.”

“I’m a senior, almost a student nurse, 18 years old, black hair, brown eyes, and 5’ 4 ½” tall,” she wrote in letter one. “P.S.: “Write when you have time—”

Bill stayed busy in battle: search and destroy, snipers, ambushes, air strikes, VC that “melt away” in the mist, the retrieval of body parts of men he knew. But he found time to write during spurts of calm that were flanked by the flashpoints of war.

“I waited for his letters! I was very excited,” recalls Nancy. “I might go a week without getting a letter, and you just didn’t know. He might’ve been killed. I read where the average life span of a Marine Corps machine gunner was two weeks.”

Nancy’s letters to Bill arrived by chopper. The anxious glance for an Evansville postmark. The onion skin envelopes crinkling with freshness in the jungle heat, delivering sweet daydream relief within otherwise nightmare. He’d read her words: “I went down to the river Tuesday night and watched the annual fireworks. Beautiful is all I can say to describe the color, the breathtaking pride I felt thinking of you and the rest of the men who are fighting to m ake July 4th fireworks possible for us at home.”

ake July 4th fireworks possible for us at home.”

The start of Nancy’s stream of letters couldn’t have come at a better time. In March of ’67, Bill’s company was ambushed, leaving scores of fellow Marines dead or injured. A week later, he witnessed booby traps kill several fellow survivors of the ambush. His company reformed in Da Nang, reinforced mostly with recruits fresh from the States.

“They were scared,” the Pennsylvanian turned Hoosier recalls. “They had heard what had happened to the guys they replaced. We were in the mountains on a bare hill with a bunch of sandbags around it, maintaining our machine gun positions, keeping watch. Wild pigs would be running around in the brush. If they’d hear movement, they’d let loose with their M60 machine guns, risking the lives of our own men. I talked to them, calmed them down. The only thing to talk about was women.”

One of those new recruits that Bill tried to calm down was named Don, who hailed from Evansville. He asked Bill if he’d like to write to an Indiana girl. At the time, Don was writing to a girl named Nancy who had a friend named Debbie. Bill liked the idea. Don mailed Bill’s picture to Newburgh for Nancy to show to Debbie.

The first letter Bill received was postmarked May 25, 1967. It was from Nancy, not Debbie. Itbegan, “Dear Bill, I’m sorry to disappoint you but Debbie was asked to go steady last week, so I guess you and Don are both stuck with me…Hope you don’t mind me writing. I thought the only privilege better than writing one Marine would be to write two Marines!”

Earlier, Nancy sent a photo to Don showing her standing in the snow in a two-piece bikini holding a beach ball. “Don was just a friend, nothing romantic,” she recalls. Don showed it to Bill. “I’d definitely like to write to this girl,” he recalls thinking.

“It took a lot of scared moments, luck, prayers . . . to get me to today,” he wrote inhis first letter to Nancy on May 30. “I got my promotions fast but I’ve had to see too many friends die and get hurt. Viet Nam is a beautiful place to look at, someday maybe it will be a tourist country, but now it’s a place where you see poor people striving to exist, where cunning people strive to cheat, where an enemy strives to kill, from 115-degree heat to teeth-chattering rain, cold, rice paddies, mountains, sand, brush land, mud, swamps, jungle, bugs that’ll carry you off if you aren’t careful, to tigers.”

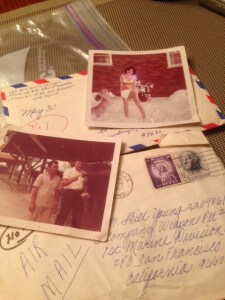

They saved all their letters to this day. They’re scattered around my slice of apple pie on their dining table. A couple hundred correspondences maybe, introductory letters that swiftly turned into love letters, a volley of hearts from one side of the world to the other, from Newburgh to ‘Nam, ‘Nam to Newburgh. She mailed her locket to him. He wrote, “Seven hours ago, I took the locket from your letter. Four hours ago, we fought our way out of a sniper’s ambush. It was hanging on my neck among my dog tags flowing among the sweat on a bare chest, next minute it was floating in rice paddies, water and mud . . . I kid you not, while I fired a 100 rounds and was changing ammo, all I could think of was your next letter and when I could feel a hand instead of paper . . . Those four big letters, that one word on the front, makes me want to wear it to hell and back.”

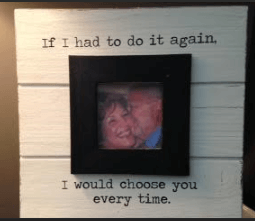

In October of ’67, they met for the first time at the Evansville airport when Bill was on leave. They were engaged a year later, married Dec. 21, 1968 and resided in southern Indiana to be close to Nancy’s family. They now live on a peaceful piece of wooded rural route land outside Rockport. After the military, Bill was a Pinkerton detective, then taught at Lockyear College in Evansville, and ultimately landed a finance job with Kimball International until recent retirement. Nancy, a lifelong nurse, currently serves as a hospice nurse. Their children are grown. They are grandparents. Nancy sorts thru the mound of letters with me. “Mom thought I was crazy, but sometimes you can get to really get to know somebody better when they are really writing their feelings and what they think about. In a letter you can be your real self. I got to know him pretty well, and he got to know me pretty well.

“At first, I felt a need to do something to ‘help’ our soldiers fighting in Vietnam. I grew up watching nightly news during our dinner hour. There were interviews by the war correspondents, pictures of boys in the mud during monsoons, rice paddies, body bags, etc., every night! There were the protesters, Jane Fonda and the Viet Cong. It made me sad for all the suffering these men were going through. It felt like the least I could do, to try and raise their spirits, to send a little care from home. Then, of course, I got to know Bill through his letters. He shared so much of what he was actually going through, how he felt, and I fell in love with that young Marine. Wasn’t hard to do. Our love continues to grow.”

A January sun sets behind a scribble of snow-covered Spencer County forest, bringing a fiery glow to the red Marine flag on Bill’s back porch. He’s bearded, has been since the deadliest of days containing the aforementioned ambush. He keeps the beard in honor of those who died that day. A Lock Haven, Pa., native, Bill worked at F.W. Woolworth until seeing a Marine recruitment poster showing a male Marine flanked by two attractive female Marines. Fueled by hormones and heroics, he volunteered immediately, his main intent being to go to ‘Nam.

“I have not looked at any of these letters since the war,” he says.

“Why not?”

“Partly because you know you are 20 and you are still gung ho. The war was John Wayne and apple pie at that time (until the Tet Offensive erased public support for U.S. involvement). As a machine gunner, you pulled the trigger—there would be targets. I don’t want to read about that anymore. I just don’t.”

But Bill’s reluctance to read them doesn’t undermine what the letters represented. “It was to keep the san eness. It was a touch of reality, a touch of something good. As far as how we got together, it was magic. One letter led to another letter. Next thing I remember, we are getting married.”

eness. It was a touch of reality, a touch of something good. As far as how we got together, it was magic. One letter led to another letter. Next thing I remember, we are getting married.”