Bud Wentz and the Great Big Whump: A World At War

Budd Wentz and the great big whump: A World at War

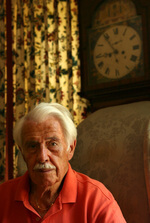

Dr. William “Bud” Wentz in his Shaker Heights home on Tues. July 29, 2008. As a WW II B-17 pilot, Wentz was once shot down and rescued, and once had his plane rammed by a German fighter. (Thomas Ondrey/The Plain Dealer)

On April 7, 1945, as W. Budd Wentz piloted his B-17 bomber to a targeted airfield in Germany …

“I just felt this great big whump, and the airplane swayed back and forth, and there was a lot of metallic noise in the back. All four engines were functioning, the airplane was still flying OK, so I figured, well, we got hit by something, but everything seems OK.

“Then the [waist] gunner called and said, ‘The tail turret’s gone and shoved the tail gunner 10 feet up the fuselage. There’s a lot of damage back there, and there are pieces flying off the airplane.’ And the engineer climbed up into the top turret and said, ‘You don’t have any rudder anymore.’ ”

It wasn’t until 58 years later that Wentz, now 83, of Shaker Heights, learned from an author writing a book about his bomb group that his plane was one of many B-17s deliberately rammed by enemy fighters that day.

The effort was part of a last, desperate bid by German Luftwaffe air forces in the waning months of World War II to bring down American bombers by any means possible. (Wentz and other bomber pilots hit by German fighters were featured in the History Channel’s “Dogfight” TV series, titled “The Luftwaffe’s Deadliest Mission.”)

In one sense, that startling mission was a fitting cap to Wentz’s combat flying career, which began just as colorfully.

Six months before the fighter hit his plane, Wentz was piloting his first bombing mission when, hit by anti-aircraft fire, he had to drop out of formation after one of the B-17’s engines failed. He jettisoned the bombs to maintain altitude, then a second engine quit. The crew tossed machine guns, ammo and anything heavy overboard to keep their height up. A third engine sputtered just after Wentz ordered the crew to start bailing out.

“Four engines are nice. Three’s OK. Two, eh. One, you have to get on the ground. None, you’re gonna get on the ground. A B-17 is not a glider,” he recently said, recalling the mission.

The fourth engine quit just as Wentz landed the bomber in a Belgian pasture, behind enemy lines. Fortunately they were immediately met by partisans, who escorted the bomber crew to safety after a few tense days spent hiding in a small village.

Wentz’s initiation to war amply proved there was a lot more to combat aviation than flying.

The Philadelphia native had enlisted in the Army Air Corps rather than leave his fate to the vagaries of the draft. “I wanted to learn how to fly, and I thought that was the cheapest way to learn,” he said.

He was attending the University of Pennsylvania when the war started, planning to become a doctor. (It was a goal he would accomplish after the war, attending medical school and serving as a professor at Case Western Reserve University’s medical school until he retired in 1989. He’s now a professor emeritus.)

In the service, Wentz initially trained to fly B-24 bombers but switched to B-17s when he went to England to fly with the 487th Bomber Group of the Eighth Air Force.

He soon learned the intense concentration, and risks, of flying in a tight formation of bombers committed to following a straight and level course so the maximum number of bombs could be concentrated on a target.

In doing so, they flew directly into the sights of German fighters and anti-aircraft guns. “Predictable moving targets,” as Wentz described the bombers’ lot.

Anti-aircraft flak was worse than fighters, “because there was so much of it,” Wentz added.

But it was a fighter that put Wentz on a white-knuckled path back home, while flying the bomber he had dubbed “My Best Bette” for his fiancee, who later became his wife of 63 years and mother of their three children.

Wentz said that after the fighter hit the tail of his B-17, he went through a familiar routine. Dropped out of formation, jettisoned his bombs, told his crew to don their parachutes and looked for a place to land the crippled aircraft.

Fortunately he found one — the last one he’d ever need, as it turned out. Wentz recalled that following the ill-fated flight, his commanding officer told him that after 28 missions and two forced landings, the luck of the “My Best Bette” crew seemed to be wearing thin, so he was sending them home. Wentz got back to the United States the day Japan surrendered, ending World War II.

Though Wentz said he never doubted the Allies would ultimately win the war, he wasn’t sure he’d be around to see it — particularly as Eighth Air Force deaths soared to more than 26,000, about 10 percent of all Americans killed during the war.

“I didn’t think I was going to make it. I was very pessimistic toward the end,” he said. “Looking at the statistics, and knowing your chances weren’t real good, what other way can you look at it?”

http://blog.cleveland.com/metro/2008/08/budd_wentz_and_the_great_big_w.html